GWPF | 8 Oct 2015

India Will Oppose The Paris Text, Environment Minister Announces

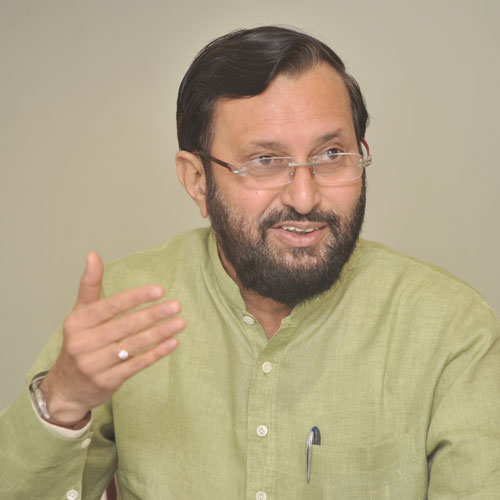

India on Wednesday expressed disappointment over the first draft text of the Paris climate change agreement, which was presented to the governments two days ago, and said the country would oppose it during the next round of negotiations at Bonn. In his first reaction to the draft text that completely ignores the crucial issue of ‘equity’ and transparency of action, environment and climate change minister Prakash Javadekar said, “I would like to underline that the first draft text of the Paris agreement is quite disappointing. It does not inspire.” He told the TOI that he was “not at all happy” with the text and the Indian negotiators would certainly oppose it during the next round of negotiations in run-up to the Paris conference. –Vishwa Mohan & Rajeev Deshpande, Times of India, 8 October 2015

1) India Rejects Draft Text For UN Climate Deal – Times of India, 8 October 2015

2) India Will Oppose The Paris Text, Prakash Javadekar – Times of India, 8 October 2015

3) Limping To Paris: New Draft Climate Text Is 20 Pages of Hedging – The American Interest, 5 October 2015

4) Peter Foster: Paris’s Scary Climate Agenda – Financial Post, 7 October 2015

5) New Paper: Weather Extremes Don’t Harm Insurance Companies – Bishop Hill, 7 October 2015

6) Editorial: British Steel’s Green Death – The Wall Street Journal, 7 October 2015

You can be sure that many countries will be pushing for those less stringent, bracketed options. Take India, which last week outlined its climate pledge, a pledge that essentially amounted to a promise to only triple its carbon emissions by 2030, a reduction from the seven-fold increase unfettered growth might otherwise produce. India isn’t the only nation keen on choosing development over green goals. Coal-dependent Poland has already staked out a similar position, and that sentiment will be forcefully expressed by many of the world’s poorer countries in Paris. The summit may have a shorter text, but if the new draft has accomplished anything, it’s to throw into sharper relief the divide between the developed and developing worlds. —The American Interest, 5 October 2015

If anybody doubts the significance of the changes to which the puppeteers of Paris aspire, they should refer to remarks made last week by Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, who suggested that the climate thrust could destroy massive value as oil and gas assets are “stranded” by climate legislation. This is not the first time that Carney has addressed the risk of stranded assets. After a similar Bank of England claim earlier this year, Carney gave evidence before a House of Lords committee. Nigel Lawson, the redoubtable former Chancellor of the Exchequer and founder of skeptical think tank the Global Warming Policy Foundation, noted that the bank’s projections were entirely at odds with those of the International Energy Agency, which saw decades of fossil-fuelled growth. Lawson suggested that Carney should stick to his financial mandate, and that the Bank should stop spouting “green claptrap.” –Peter Foster, Financial Post, 7 October 2015

With “Mystic” Mark Carney telling anyone who crosses his palm with silver (or, indeed, anyone who crosses his path) that the insurance industry is going to be sunk by climate change, it’s interesting to see what the empirical evidence has to say on the subject. By happy coincidence, Ross McKitrick has just published a paper on just this subject. –Andrew Montford, Bishop Hill, 7 October 2015

Britain’s industrial heartland has been rocked by news that Thai steelmaker Sahaviriya Steel Industries, or SSI, will close its plant at Redcar in England within months. SSI is winding down its entire U.K. subsidiary at the cost of up to 2,000 jobs. Pin the blame on David Cameron’s climate policy. Belatedly recognizing what an economy-killer the carbon-price floor is, Mr. Cameron’s government last year capped the additional amount emitters would have to pay. That’s progress, but not nearly enough to save jobs. A better idea would be to scrap Britain’s war on carbon entirely. As the science surrounding climate change becomes ever more contentious—and as green industries chronically fall short of the job creation and growth they promise—the costs of anticarbon policies grow and grow, not least for those 2,000 workers at Redcar. –Editorial, The Wall Street Journal, 7 October 2015

1) India Rejects Draft Text For UN Climate Deal

Times of India, 8 October 2015

Vishwa Mohan & Rajeev Deshpande

NEW DELHI: India on Wednesday expressed disappointment over the first draft text of the Paris climate change agreement, which was presented to the governments two days ago, and said the country would oppose it during the next round of negotiations at Bonn.

In his first reaction to the draft text that completely ignores the crucial issue of ‘equity’ and transparency of action, environment and climate change minister Prakash Javadekar said, “I would like to underline that the first draft text of the Paris agreement is quite disappointing. It does not inspire.”

He told the TOI that he was “not at all happy” with the text and the Indian negotiators would certainly oppose it during the next round of negotiations in run-up to the Paris conference.

The draft agreement is a concise basis for negotiations for the next session from October 19-23 in Bonn. Co-Chairs Ahmed Djoghlaf of Algeria and Daniel Reifsnyder of the US prepared the draft in response to a request from countries to have a better basis from which to negotiate.

Without going into the details of the text and India’s specific objections, Javadekar said, “We should certainly have a different text for the Paris meet to become a success. Our negotiators will submit India’s suggestions. Other countries will also come out with their suggestions.

“This is, after all, not a final text. I hope that there will be more moderated and justifiable text on table after Bonn and other pre-COP (conference of parties) negotiations. I wish the things will improve in the run-up to Paris.”

Full story

2) India Will Oppose The Paris Text, Prakash Javadekar

Times of India, 8 October 2015

Vishwa Mohan & Rajeev Deshpande

Expressing reservations over the draft agreement for the climate summit in Paris next month, environment, forests and climate change minister Prakash Javadekar said he will seek changes that are in tune with the developing world’s expectations and suggested the developed nations must do more.

Q. India last week submitted its INDC which were well received due to ambitious targets. Can the goals be achieved?

A. We have done quite an elaborate exercise to prepare our INDC (post-2020 climate action plan). It is comprehensive and ambitious. We have already taken a number of measures to increase our carbon sink through a massive afforestation drive. We will spend over Rs 2 lakh crore to increase forest cover in coming years. Our target to reduce emission intensity of GDP by 33-35% by 2030 from 2005 level and our goal to increase share of non-fossil fuel based energy resources by about 40% by 2030 are practical and pragmatic. It is now time for the developed world to ramp up their targets, keeping their historical responsibilities in mind. They should tell us what they all are doing as part of their pre-2020 actions. They should not have a five year ‘action holiday’ (2015-20).

Q. Rich nations, including the US, have submitted respective INDCs. But, these pledges together cover only about 87% of emissions. How will you move towards Paris (COP21) with such low ambition?

A. That’s why we are questioning developed countries and asking them come out immediately with their pre-2020 actions. After all, it was their historical emission (during 1850-2011) that led to 0.8 degree Celsius temperature rise in the post-industrialization phase. They must act and lead by example. I would also like to ask the rich nations to vacate carbon space for us (developing and poor countries). We want the rich nations to take care of their ‘lifestyles’ (excessive consumption) so that it can ensure ‘climate justice’ for poor people in the world.

Q. What kind of outcome you are looking at Paris climate conference in these circumstances?

A. We want Paris to be successful because we care for climate and care for poorer sections of the world. I would, however, like to underline that the first draft text of the Paris agreement (released two days ago) is quite disappointing. It does not inspire. I am not happy with the text. We should certainly have a different text for the Paris to become success. Our negotiators will oppose this first draft text during the next round of negotiation at Bonn. Our negotiators will submit India’s suggestions. I hope there will be more moderated and justifiable text on table after Bonn and pre-COP negotiations. I wish the things will improve in the run up to Paris.

3) Limping To Paris: New Draft Climate Text Is 20 Pages of Hedging

The American Interest, 5 October 2015

At long last, negotiators have hammered out a condensed draft text for this December’s climate summit in Paris. Members of the UN’s catchily named Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action took a bloated 86 page document and slimmed it down considerably. But a quick reading of the text evinces the fact that brevity and clarity are not the same thing, as plenty of uncertainty remains in the form of bracketed verbiage.

Here’s a sample of the first heading under the Mitigation section of the text, which is sure to be one of the most contentious items under discussion during the conference:

Parties aim to reach by [X date] [a peaking of global greenhouse gas emissions][zero net greenhouse gas emissions][a[n] X per cent reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions][global low-carbon transformation][global low-emission transformation][carbon neutrality][climate neutrality]. […]

Each Party’s nationally determined mitigation [contribution][commitment][other] [shall][should][other] reflect a progression beyond its previous efforts, noting that those Parties that have previously communicated economy-wide efforts should continue to do so in a manner that is progressively more ambitious and that all Parties should aim to do so over time. Each mitigation [contribution][commitment][other] [shall][should][other] reflect the Party’s highest possible ambition, in light of its national circumstances, and: (a) [Be quantified or quantifiable;] (b) [Be unconditional, at least in part;] (c) [Other].

To take one example, the difference between the words “shall” and “should” in an international treaty is obviously enormous, the former being presumably binding while the latter describes a suggestion for the involved parties. It’s not surprising that these differences haven’t been ironed out yet—that’s a job for the delegates due to descend on Paris—but this draft text is lousy with these sorts of opportunities for equivocation.

And you can be sure that many countries will be pushing for those less stringent, bracketed options. Take India, which last week outlined its climate pledge, a pledge that essentially amounted to a promise to only triple its carbon emissions by 2030, a reduction from the seven-fold increase unfettered growth might otherwise produce. India has long insisted on its right to grow and as Reuters reports, it’s planning on doing that with the help of cheap, dirty coal:

India is opening a mine a month as it races to double coal output by 2020, putting the world’s third-largest polluter at the forefront of a pan-Asian dash to burn more of the dirty fossil fuel that environmentalists fear will upend international efforts to contain global warming. […]

If India burns as much coal by 2020 as planned, its emissions could as much as double to 5.2 billion tonnes per annum – about a sixth of all the carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere last year – [said Glen Peters at the Center for International Climate and Environmental Research]…He said India could replace the United States as the world’s second largest emitter by 2025. “This is something no one would have expected.”

India isn’t the only nation keen on choosing development over green goals. Coal-dependent Poland has already staked out a similar position, and that sentiment will be forcefully expressed by many of the world’s poorer countries in Paris. The summit may have a shorter text, but if the new draft has accomplished anything, it’s to throw into sharper relief the divide between the developed and developing worlds.

4) Peter Foster: Paris’s Scary Climate Agenda

Financial Post, 7 October 2015

In a speech last week, Pope Mark claimed that “climate change will threaten financial resilience and longer term prosperity.” But the primary threat comes not from climate change, but from climate change policy.

Details of two international agreements were released on Monday. One, the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which reduces trade barriers between 12 signatories, including Canada, got lots of ink. The other, which purports to control global weather, end the era of fossil fuels, and place all human activity under bureaucratic control, got very little.

Excerpts from a “Draft Agreement” and “Draft Decision” released Monday, Oct. 5, by the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, to be used as a the basis for negotiation of the draft Paris climate package.

The pretensions of the latter text, released by the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action, ADP, which is assigned to come up with an agreement to put to the vast UN climate meeting in Paris in December, are mind-boggling. The fact that they attracted little attention means either that the media and public have no idea of the climate agenda’s implications, or that nobody takes the agenda seriously. Probably both. After all, the UN has been promoting the “urgent threat of climate change” for more than 25 years.

While the text of the TPP has yet to be finalized, that of the Paris meeting is skeletal. But, like skeletons, it is scary.

If anybody doubts the significance of the changes to which the puppeteers of Paris aspire, they should refer to remarks made last week by Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, who suggested that the climate thrust could destroy massive value as oil and gas assets are “stranded” by climate legislation.

Carney, former Governor of the Bank of Canada, has been lauded by segments of the Canadian mainstream media as a “rock star.” Indeed, he does bear some similarity – at least in orientation — to icon Neil Young, who has become deranged over the oil sands and recently signed his name to Naomi Klein’s loopy Leap Manifesto.

Carney would perhaps see his status as more analogous to another anti-capitalist crusader, Pope Francis, the man who put the “vestment” in “divestment.”

In fact, this is not the first time that Carney has addressed the risk of stranded assets. After a similar Bank of England claim earlier this year, Carney gave evidence before a House of Lords committee. Nigel Lawson, the redoubtable former Chancellor of the Exchequer and founder of skeptical think tank the Global Warming Policy Foundation, noted that the bank’s projections were entirely at odds with those of the International Energy Agency, which saw decades of fossil-fuelled growth. Lawson suggested that Carney should stick to his financial mandate, and that the Bank should stop spouting “green claptrap.” (Significantly, the draft Paris text cites “financial institutions” as key partners in its fight against capitalism. Meanwhile Carney isn’t just boss of the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street, he is head of the Financial Stability Board, a global organization of central bankers. He is reportedly to push the climate agenda at a G20 meeting in November).

The Paris text’s most significant feature is its lack of detail. It starts with the suggestion that the parties recognize “the intrinsic relationship between climate change, poverty eradication and sustainable development.”

But although the relationship may be intrinsic, it is far from clear. Insofar as the promoters of the agreement seek to starve poor countries of financing for “maladaptive” fossil fuel development, they are promoting poverty. Developing countries want nothing to do with having wind and solar foisted on them. They are gung ho for coal. They are also interested in the annual US$100 billion of handouts, starting in 2020, that was promised six years ago at Copenhagen but that, true to form, has not materialized.

The negotiating text betrays that peculiarly UN mindset that demands that all the world’s alleged problems be shouldered and addressed together, a kind of Gethsemane Syndrome. Not only will a giant interlinked series of new bureaucracies oversee programmes to regulate the climate and encourage appropriate technology and development to end poverty. They will negotiate these joint wonders while ensuring sensitivity to women, natives and the disabled. Their call to action claims to be based on “the best available scientific knowledge,” yet it also incorporates “traditional” — that is, distinctly non-scientific — knowledge.

Among additional “preambular paragraphs” being considered is a reference to “Mother Earth.” This is not just a spiritual add-on. As a provider of “environmental services” Gaia needs to be paid. Since she has no bank account, the UN is more than prepared to act as her proxy.

The document is a compendium of parentheses, that is, wording or issues that have yet to be decided. One parenthesis suggests that the famous 2 degrees Celsius rise in global temperatures (since before the Industrial Revolution) that will put us at an existential tipping point might be changed to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Could that be a recognition of the inconvenient fact that global temperatures are refusing to rise despite unprecedented increases in the CO2 that is meant to drive them?

The desperation to negotiate a deal is obvious in provisions that signatories may be able to pull out after three years, and that there are no penalties for non-compliance.

The document is very big on “capacity building,” which means bureaucrats teaching people to think like them, in terms of “modalities and procedures” and “facilitative dialogues.” Best practices are a top priority, particularly if they are “scalable and replicable.” Needless to say, the world’s most obscure document is big on transparency.

In that speech last week, Pope Mark claimed that “climate change will threaten financial resilience and longer term prosperity.” But the primary threat comes not from climate change, but from climate change policy.

The Paris text several times stresses the critical importance of cities and non-governmental organizations in promoting the climate agenda. Thus, to the extent that Canadian export pipelines are being opposed by local authorities in Vancouver and Montreal, and challenged legally and illegally by the likes of Greenpeace and ForestEthics, the UN’s agenda isn’t just bureaucratic fantasy. It’s a real threat to prosperity and democracy.

5) New Paper: Weather Extremes Don’t Harm Insurance Companies

Bishop Hill, 7 October 2015

Andrew Montford

With “Mystic” Mark Carney telling anyone who crosses his palm with silver (or, indeed, anyone who crosses his path) that the insurance industry is going to be sunk by climate change, it’s interesting to see what the empirical evidence has to say on the subject. By happy coincidence, Ross McKitrick has just published a paper on just this subject.

Here’s what he says about it on his website.

Bin Hu and I have just published a study looking at how climate variations, in particular indicators of extreme weather, have historically affected the share prices of major insurance firms. The insurance industry has raised the concern that climate change poses a financial risk due to higher payouts for weather-related disasters. However, if extreme weather is increasing, presumably that means they have an opportunity to sell more insurance products as well, which may increase profitability. In our paper we examined historical data on a portfolio of insurance firms and estimate a three-factor model augmented with climate indicators. Short-run deviations in measures of climate extremes are associated with increased profitability for insurance firms. Overall we find that past climatic variations have not had a negative effect on the profitability of the insurance industry.

6) Editorial: British Steel’s Green Death

The Wall Street Journal, 7 October 2015

Another 2,000 lost jobs are collateral damage in the war on carbon dioxide. Pin the blame on David Cameron’s climate policy.

Britain’s industrial heartland has been rocked by news that Thai steelmaker Sahaviriya Steel Industries, or SSI, will close its plant at Redcar in England within months. SSI is winding down its entire U.K. subsidiary at the cost of up to 2,000 jobs. Pin the blame on David Cameron’s climate policy.

The company hasn’t attributed its decision directly to environmental regulations, citing instead growing competition from cheaper Chinese steel and slack demand as developing economies around the world start to falter. But the converse of saying Chinese steel is too cheap is that British steel is too expensive. Why?

Start with a suite of renewable-energy policies that keep ratcheting up electricity costs. The so-called renewables obligation, which requires utilities to buy a steadily increasing share of their power from trendy green sources such as solar and wind, is driving up wholesale power prices. So is the feed-in tariff, which forces utilities to pay a minimum rate for renewable electricity that’s higher than the cost of fossil-fuel-fired generation.

Meanwhile, Britain since 2013 has imposed a floor price on carbon-dioxide emissions that’s higher than the cost elsewhere in Europe. Under the European Union’s emissions-trading system, in which Britain participates, manufacturers such as steelmakers and electricity generators already are required to buy credits equal to their annual emissions.

On top of this, Mr. Cameron’s government set a minimum price per ton of emissions, starting at £16 in 2013 and originally intended to increase to £30 in 2020. In any year that the price of a European emission credit falls below London’s preferred level, London levies a tax to make up the difference.

As European carbon prices have plummeted amid declining economic activity and Britain’s price floor has increased, British companies and consumers at times have had to pay up to six times more than their European peers per ton of emissions. The EU’s emissions scheme itself makes European energy more expensive than most other parts of the world.

This all trickles through to higher electricity prices. Out of a total electricity cost of £90 ($136.70) per megawatt-hour for a large consumer in 2015, Britain’s renewables mandate accounts for around £13 while the carbon-price floor accounts for another £10, according to the Energy Intensive Users Group, an organization that represents large manufacturers. All climate policies together add more than 50% to the price of electricity for large industrial users.

That hurts all companies and households, but disproportionately wallops energy-intensive industries such as steel. Britain’s heaviest industrial-power consumers paid 9.3 British pence per kilowatt hour for electricity in the second half of 2014, according to EU data, compared to an EU median of 5 pence. Subsidies to large industry partly compensate for the higher costs of the carbon-price floor, but not for the renewables mandates.

SSI’s closure is the latest consequence of policies that drive up energy costs, but it’s not the first. Tata Steel has announced more than 700 layoffs this year as it reduced or suspended production at plants in Wales and northern England. Tata’s chief executive for Europe, Karl Koehler, is clear about why: “Energy is one of our largest costs at our speciality and bar business and we are disadvantaged by the U.K.’s cripplingly high electricity costs,” he said in July.

Belatedly recognizing what an economy-killer the carbon-price floor is, Mr. Cameron’s government last year capped the additional amount emitters would have to pay at £18 per metric ton of emissions at least until 2020. That’s progress, but not nearly enough to save jobs when a ton of emissions under the Europe-wide trading scheme costs only £6, and the cost is zero in most of the rest of the world. London’s only other brain wave appears to be to promise subsidies to help offset companies’ higher energy costs.

A better idea would be to scrap Britain’s war on carbon entirely. As the science surrounding climate change becomes ever more contentious—and as green industries chronically fall short of the job creation and growth they promise—the costs of anticarbon policies grow and grow, not least for those 2,000 workers at Redcar.

See also: UK Steel Crisis: GWPF Calls On Government To Scrap Carbon Floor Price