Sharyl Attkisson | 25 May 2022

The following is a news analysis

Near the end of the documentary 2000 Mules, the filmmakers and their advocates anticipate the partisan criticism the film would draw.

“They have two ways they’ll try to invalidate it,” predicts conservative leader Charlie Kirk. “One is minimizing. And then slander.”

Then, speaking to cell phone data used to prove the alleged crimes, conservative military and intelligence analyst Sebastian Gorka adds, “I predict right now they will say, ‘What on earth is a conservative doing tracking private citizens? Gee how dare they? What is Dinesh D’Souza doing to voters? At 3 AM?’ And that will be part of it.”

Attorney Larry Elder adds, “This is a smoking gun. This is OJ Simpson being seen leaving the scene of the crime.”

It seems significant to remember that a jury found OJ Simpson not guilty of murdering his ex-wife and her friend. He was later found Iiable for wrongful death in the same double murder as the result of a civil trial.

Smoking guns aren’t always cut and dry.

In any event, the response to 2000 Mules has been swift and largely predictable. Trump advocates insist it proves game-changing election fraud in 2020. Trump opponents claim it’s just another debunked conspiracy theory that proves nothing.

In the predominantly left-leaning establishment news media, the figures who have addressed the documentary tend to promote the latter conspiracy theory interpretation— advising people not to see the film, while simultaneously assuring them there’s nothing to see.

Meantime, it seems clear that many who are publicly commenting, including some of the harshest critics, haven’t actually watched the film.

Watch the trailer for 2000 Mules

So we’re left with a documentary that— if the evidence is true—would be one of the most important and impactful films of its time, but is likely being viewed almost exclusively by those in no need of conversion.

There was a time prior to 2015, before Donald Trump entered national politics, when the forensic work described in the film would have been done by credible news organizations and journalists, and by independent law enforcement bodies.

Those days are gone.

Most of the news media issued a collective shrug in the face of an election that was at the very least unusual, with unprecedented changes made under the auspices of Covid, with intervention by billionaire third party activists pouring money into projects like drop boxes, with positions and final calls getting switched, with polls that were wrong, with ballots that had no chain of custody, with a flood that never actually occurred but stopped counting at a Georgia precinct until the Republican observers went home, and much more.

Worse, some in the media insisted that questions and suspicious happenings should not be investigated even if the outcome would reassure a skeptical public the election was fair. To feel otherwise, we were told, was to be a conspiracy theorist of the worst kind bent on treason or the fall of democracy itself.

Journalists and political figures declared, without evidence, that there was no fraud. When fraud emerged, they said there was no widespread fraud. When there was evidence of widespread fraud, they said there was no widespread fraud that would have changed the results. Yet they had no firsthand investigation to support these positions. Whenever opposing claims were made or differing intepretations were possible, they sided with one and called the other “conspiracies,” as if they hadn’t noticed that, in the prior four years, so many conspiracies had proven true, and so many declared truths had proven false.

Law enforcement investigators did no better.

So, today, we’re left with a partisan group that did what nobody else wished to do and turned it into a film.

They unearthed and dug into data that anybody willing and able to spend the time and money could have gotten– and could still get. The data reveals, they contend, a coordinated election fraud operation prior to election day that flipped the results.

For those who are curious to know more about what’s presented in the film, this summary and analysis are offered. However, if you’re interested in this topic, I advise you to see the film and make up your own mind.

First, I think it is worthwhile. Second, it is common for people to form a firsthand take-away that differs from other people’s. In my own experience, I find myself rarely in agreement with popular analyses of news events and editorial content.

Learning the information in 2000 Mules cannot hurt you. You are free to gather it and — as my grandmother used to say— take the information, “chew it up, swallow what you like, and spit out the rest.” Or, in less colloquial terms: believe all of what’s in the movie, part of it, or none of it. It’s your choice.

Please note: This analyzes and summarizes information as presented in the documentary and is not intended to serve as independent verification.

Title

2000 Mules is named for 2,000 alleged illegal ballot carriers or “mules” in the 2020 election as identified in the film.

Players

Dinesh D’Souza narrates and serves as the film’s anchor. Born in India, he is a conservative filmmaker, speaker, and author who once advised President Reagan. He hosts a podcast sponsored by Salem Media.

Charlie Kirk is an author and speaker who started and heads up the student empowerment group Turning Point USA.

Sebastian Gorka is a British-born Hungarian-American military and intelligence analyst who advised President Trump.

Dennis Prager is a conservative radio talk show host who founded PragerU, an online site that produces videos in support of freedom, democracy, fairness, equality, and conservative principles.

Eric Metaxas is a Christian author, speaker, and radio host.

Larry Elder is an attorney and talk radio host. He lost the 2021 race for governor of California in the recall election of Gov. Gavin Newsome.

Debbie D’Souza is Dinesh’s wife. Her appearance in the film seems to be explained by the fact that she introduced her husband to Catherine Englebrecht (below) and was a poll watcher who identified improper practices some years ago.

Catherine Engelbrecht started and heads “True the Vote,” a pro-election integrity group targeted in the Obama administration IRS scandal. True the Vote launched the data analysis project and claims to have “the largest store of election intelligence for the 2020 elections in the world.”

Gregg Phillips is an election and data analyst working with True the Vote. He formerly headed the Mississippi Department of Human Services. He describes having captured election fraud, including vote harvesting and vote trafficking in the past by a Republican, forcing a new election.

Format

Much of the film’s story is told through roundtable discussions with two groups.

The first group is comprised of Dinish D’Souza and some of his colleagues who are also radio talk show hosts employed by Salem Media. At the start, they give their views on allegations of 2020 election fraud. At the end of the film, they discuss their opinions in light of the evidence presented. At that time, they universally express alarm, and indicate they are convinced there was widespread and meaningful fraud.

The second group, also led by D’Souza, is comprised of his wife, Debbie; and True the Vote’s Catherine Engebrecht and Gregg Phillips. They present background, methodology, and findings. They also talk through descriptions of mobile phone location and tracking data, and surveillance video, and calculate the ultimate impact on the 2020 election.

Through the conversations, the following was established or claimed:

When trying to find evidence of election fraud, Englebrecht explains that the privately-funded drop boxes, location data, and surveillance video were chosen as a provable, trackable target.

In two of the five states examined, ballots can legally be delivered by a family member or care giver (“vote harvesting”). But in all states, “ballot trafficking” is illegal. In other words, nonprofits and others may not collect ballots and give them, or pay, to have them delivered to drop boxes.

Cell phones deliver location and time data to hundreds of thousands of apps. The data is used by military, law enforcement and intelligence. The data is also sold to brokers, who resell the data.

True the Vote spent over $1 million to purchase ten trillion signals in selected battleground cities and states. The data was purchased around election drop boxes, where surveillance cameras were also supposed to be monitoring.

True the Vote also obtained four million minutes of publicly-available surveillance video of drop boxes through open records requests. The video dates from Oct. 1, 2020 through the presidential election or, in the case of Georgia, through the state’s Jan. 6, 2021 runoff.

True the Vote looked for people who directly visited 10 or more drop boxes and made five or more visits to nonprofit organizations or “stash houses” that presumably collected, produced, and/or handed out ballots and/or paid the “mules.”

The relatively high number of drop box and nonprofit visits required to fit the film’s definition of a “mule” was intended to establish an extremely high bar and leave less room for error.

The mules may have been paid $10 per ballot. It’s believed they were sometimes required to produce photographs of the drop boxes or their actions in order to get paid.

Surveillance video of drop boxes was required by law but was turned off or not available on certain drop boxes in Arizona, Wisconsin, and Fulton County, Georgia.

Survillance Video

The film highlighted the following clips from publicly-available surveillance video.

In Atlanta: One person who went to 28 drop boxes and 5 nonprofits in one day.

In Gwinnett County, Georgia: Election officials with duffel bags containing 1,962 ballots which, according to chain of custody documents were deposited by just 271 people during 25 hours.

In Georgia: A woman with S.C. plates stuffing 3-4 ballots into a box. She visited dozens of drop boxes during the general election and the runoff. She showed up wearing gloves starting Dec. 23, 2020 just after news the FBI had caught ballot-stuffers in Arizona based on fingerprint evidence. After putting ballots in the drop box, she removes her gloves, and throws them into a nearby trash can.

A man approaching a drop box on his bike, pulling ballots out of his backpack, depositing them, and taking a photo.

In the middle of the day at a polling place, a man removing ballots from under his arm and a bag, putting them in a drop box, and photgraphing his actions.

Statistics

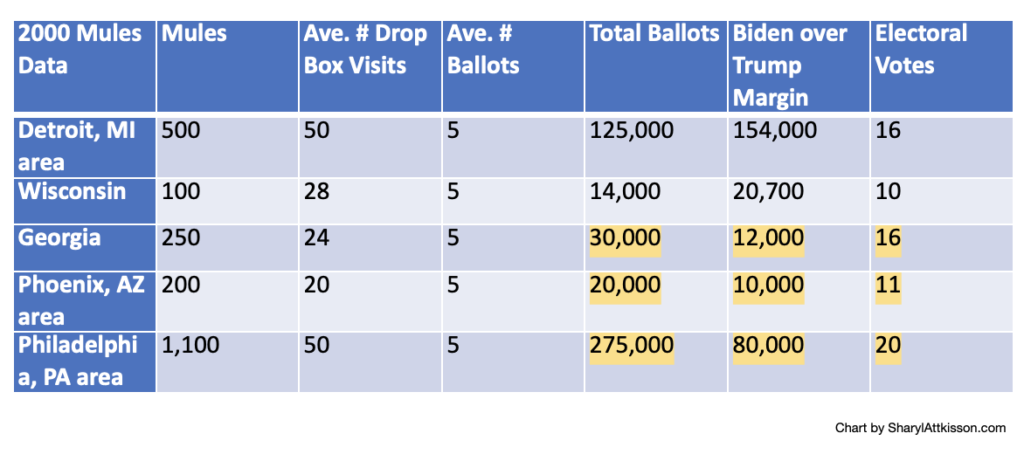

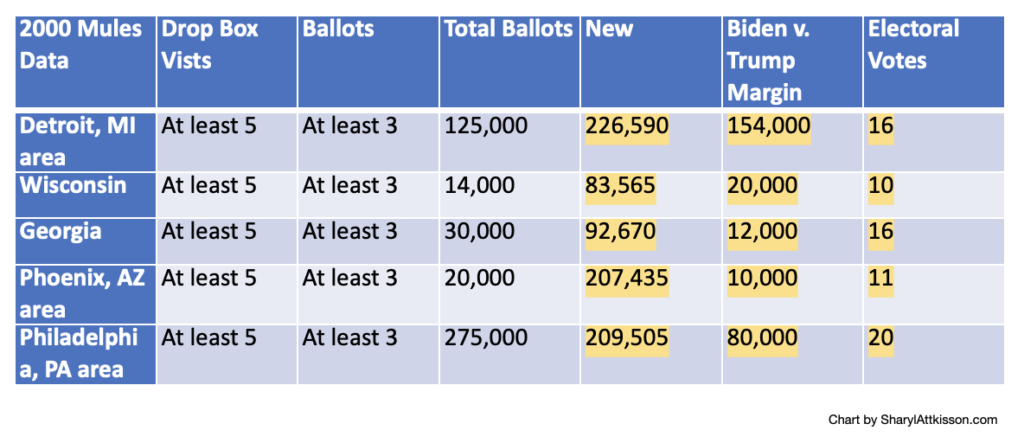

The film claims that for 2,000 illegal ballot carriers, with an average number of 38 drop box visits per person, and five ballots per visit, it amounts to 380,000 questioned ballots in five metro areas or states.

Detailed stats presented add up to slightly higher numbers: 2,150 mules impacting 464,000 ballots with a final electoral count for Trump of at least 279 to Biden’s 259. Stats calculated using a broader definition give Trump a final electoral count of 305 to Biden’s 233.

Electoral Count: Trump: 279 Biden: 259

With a lower criteria to include those who visited 5-10 drop boxes and 3 ballots instead of 5, the number of mules increases from 2,000 to 54,000.

Electoral Count: Trump: 305 Biden: 233

Weaknesses

As a matter of personal preference, I would like to have seen much more surveillance video. It’s interesting and convincing. Out of the many thousands of potential mules identified, and four million minutes of video obtained, only a relative handful were shown.

That having been said, I understand the technical challenge that must come with trying to match cell phone data precisely with people captured on surveillance video. It is impressive that the filmmakers were able to do it at all.

Interviews with two whistleblowers, including one “mule” said to be cooperating with authorities, were used with limited effectiveness. They raised more questions than providing answers, and left viewers wanting more information.

A great deal about the mechanics of the alleged fraud was left to the imagination. Who signed the payment checks— or were mules paid in cash? What were the names of the nonprofits the filmmakers knew about— or why are the names not suitable for publication? How were mules recruited? Have they done this before? (One whistleblower implied there was nothing particularly new about the fraud in this election, and that ballot fraud in their region was longstanding and well known.) Were the ballots otherwise valid (i.e. legitimate votes from real people, or manufactured ballots, or real ballots filled out by someone other than the voter)? Who won votes on the ballots for president and in local races?

The nonprofits considered to be “stash houses” were not named or described, nor was there a clear explanation as to how they were identified as potential guilty parties. Were all nonprofits, such as the YMCA, hospitals, and colleges, considered for the geofencing? Or did it only include nonprofits that would theoretically have motivation, funding, and infrastructure to pull off election fraud?

Who provided funding for the fraud, which would have cost millions of dollars in the limited area examined? Who is at the top of the organizational chain? Have they done this before?

In the case of the Republican drop box watcher who blew the whistle on Republicans failing to act upon irregularities he flagged: who did this person report to? What did that person say in response? What would be the reason why these Republicans would choose to sweep fraud under the rug?

Of course, lack of detail doesn’t disprove fraud. It is not the fault of the filmmakers that they could not answer every outstanding question. True the Vote spent a great deal of time and money to get what data and information they could get. The group did something that law enforcement and journalists could have done but chose not to. In this way, investigations that should be in the hands of those once seen as neutral parties are now left to those who can easily be dismissed by critics as partisan.

Conclusions

Both candidates received more votes than any president in American history. The 2020 election was unprecedented in many ways with process and rule changes; and anomalies reported regarding absentee voting, poll observations, chain of custody, drop boxes, signature verification, and more. But logical and rational questions were swiftly dismissed by establishment media, politicians, courts and law enforcement. Often, when critics dismissed questions, they claimed, without evidence, that the questions amounted to disproven conspiracy theories. In fact, most of the claims hadn’t been independently investigated.

One lawyer involved in a 2020 election fraud claim was scolded by a judge for presenting evidence a day or two late. On that basis, the judge excluded the evidence. The lawyer explained to the judge that voter fraud cases typically take years to build. But the court was expecting him to do it in a matter of days, without the tools to force discovery or access documents and evidence.

2000 Mules illustrates how complicated a voter fraud investigation can be, and how much time it can take to gather evidence and proof.

It is significant to note that as much of a game-changer the alleged fraud in 2000 Mules amounts to, it encompasses only one relatively small slice of potential fraud claims: pre-election drop box activity. When one considers additional possibilities, it’s not hard to see that the scope could be even more massive.

The film makes a strong case that, at the very least, law enforcement authorities should have conducted— and still should conduct– a broad investigation using similar data including and beyond the five metro areas and states examined in the film.

Investigators could also go a step further and obtain the identities of the mobile phone owners (hidden for privacy reasons from those who purchase data as was done for 2000 Mules), which allows them to potentially question thousands of people.

State and local law enforcement bodies could conduct investigations in their own regions.

Law enforcement bodies should also investigate cases where cameras required to record surveillance video on drop boxes were turned off or said to malfunction.

One complication to all of this is the notion that a majority of the American public no longer trusts those who would accomplish these investigations. Whether investigators verify or refute the information presented in 2000 Mules, they would be attacked as partisans. By not promptly conducting their own investigations in the wake of the 2020 election, they have rightly become viewed as conflicted.