Paul D. Thacker | 30 Aug 2022

COVID damages memory of grant dismissal protestors, but the Internet never forgets

The National Institutes of Health terminated part of a grant last week that funded dangerous virus research at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, through a nonprofit called the EcoHealth Alliance. But you probably already read this at Politico, Science Magazine, NPR, CNN, New York Times, and Nature Magazine, right?

Oh, I forgot. These outlets forgot to do a journalism!

The only venue that found this grant termination newsworthy was a small outlet devoted to warning about the dangers fraught from misuse of modern science: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Here’s how the Bulletin reported it:

The termination notice comes after the NIH chided EcoHealth last fall for not immediately notifying the agency after its experiments showed modified coronaviruses replicated at a faster rate in experimental mice than an unmodified virus. The agency then asked for lab notebooks and other files pertaining to the experiments, and EcoHealth reported that it would relay the request to the Wuhan Institute of Virology. According to the new NIH letters, the Wuhan institute never delivered.

After the EcoHealth Alliance’s grant with the Wuhan Institute of Virology first came to national attention two years back, it created a media firestorm when the Trump administration suspended it, and various outlets reported that the scrutiny was driven by “conspiracy theories.” But now … crickets.

New studies find that COVID-19 damages people’s thinking, which may explain why science writers at NPR don’t remember that they reported removing this grant “sets a dangerous precedent by interfering in the conduct of science.” Luckily, the Internet never forgets.

A look back at reporting on this grant.✓

The first to report on the grant’s suspension and possible termination was Sarah Owermohle with Politico, in April 2020. “The Wuhan lab is at the center of conspiracy theories alleging that the coronavirus outbreak began when the virus escaped the facility,” Owermohle reported at the time.

Dismissing the possibility of a Wuhan lab leak as a “conspiracy theory” has long been a popular media meme. However, emails came out in late 2020 showing that this labeling had been orchestrated by Peter Daszak of EcoHealth Alliance, who placed an essay in the Lancet making the “conspiracy” claim without disclosing his financial ties to Shi Zhengli of the Wuhan Institute of Virology. Daszak was aided in this endeavor by virologists who placed another essay in the journal Emerging Microbes & Infections (EMI), that made the same “conspiracy” claim, without disclosing that the authors secretly gave the “conspiracy” essay to Shi Zhengli for editing and approval.

Bouncing off Politico’s reporting, Science writers Meredith Wadman and Jon Cohen came up with a second report on the subject that attempted to call into question the legitimacy of the NIH’s grant suspension

The termination, which some analysts believe might violate regulations governing NIH, also came 7 days after President Donald Trump, asked about the project at a press conference, said: “We will end that grant very quickly.”

In retrospect, much of the reporting in this article was nonsense and rife with “experts” who had undisclosed conflicts of interest. The NIH has the right to end grants when it wants, but science writers at Science Magazine were just trying to gin up a fake controversy by floating the idea that canceling this grant might be illegal. And Science Magazine failed to disclose the financial relationships of the experts coming to Daszak’s aid: Gerald Keusch and Dennis Carrol.

Keusch told Science that canceling the grant “is the most counterproductive thing I could imagine,” while Carroll told the writing duo, “There’s a culture of attacking really critical science for cheap political gain.”

Well, there’s also a culture at Science Magazine of failing to do basic journalism.

Gerald Keusch was a co-investigator with Peter Daszak on the grant in question. Plus, he had helped Daszak orchestrate the now discredited letter in The Lancet. As for Dennis Carroll, at the time Science Magazine interviewed him, he was working behind the scenes with Peter Daszak to start the Global Virome Project, an organization set up with hundreds of thousands of dollars funneled away from a USAID project that Carroll oversaw called Predict.

Dennis Carroll now heads up the Global Virome Project, and Peter Daszak serves on the board.

“It would appear that Dennis Carrol violated federal law that prohibits the use of official resources for private gain or for that of persons or organizations with which he is associated personally,” said Craig Holman of Public Citizen when shown emails about the funding for the Global Virome Project. “The Inspector General’s office should investigate whether the law was broken and, upon finding probable cause, refer the case to the Department of Justice for prosecution.”

NPR’s Geoff Brumfiel also tripped over himself to defend Daszak’s grant by casting doubt on the theory that pandemic could have started in the Wuhan lab of Daszak’s collaborator Shi Zhengli.

But after corresponding with 10 leading scientists who collect samples of viruses from animals in the wild, study virus genomes and understand how lab accidents canhappen, NPR found that an accidental release would have required a remarkable series of coincidences and deviations from well-established experimental protocols.

“All of the evidence points to this not being a laboratory accident,” says Jonna Mazet, a professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis and director of a global project to watch for emerging viruses called PREDICT.

Like the science writers at Science Magazine, Brumfiel replicated the same mistake of failing to report the sizeable conflict of interest of his chosen expert: Jonna Mazet.

At the time Brumfiel reported this story, Mazet was working behind the scenes with Peter Daszak and Dennis Carroll to funnel money from USAID to set up the Global Virome Project. Alongside Daszak and Carroll, Mazet now serves as a board member.

Bad access arguments

When it comes to science writer articles that supported Daszak and his grant with the Wuhan Institute of Virology, you might start thinking that few if any were written without sources that had financial ties to Daszak. But that’s not always true.

In May 2020, 77 Nobel Prize winners without financial ties to Peter Daszak or the Wuhan Institute of Virology released a letter castigating the NIH for cancelling Peter Daszak’s grant. “We believe this action sets a dangerous precedent by interfering in the conduct of science and jeopardizes public trust in the process of awarding federal funds for research.” The letter spurred articles in the New York Times and NPR.

NPR fell flat on its face, however, by quoting Peter Daszak making a hoary argument and implying that cancelling the grant would disallow him access to the Wuhan Institute’s virus collection.

EcoHealth Alliance’s president Peter Daszak has told NPR that as a result, his group hasn’t just lost the ability to look for new viruses in China. They — and the many international researchers with whom they share their data – have also lost access to the vast collection of distinct coronavirus samples already collected. These include around 50 from a category that caused the 2002 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, and, now, the COVID-19 pandemic.

In fact, the Wuhan Institute of Virology had already taken down their database of samples and virus sequences in September 2019—months before this story ran. In a recent interview with The Intercept, Daszak admitted that he never had access to the Wuhan’s database. “I’ve never actually seen the database,” Daszak admitted this March. “I’ve seen pages of it from the internet, Twitter, chats. But I’ve never looked at the database.”

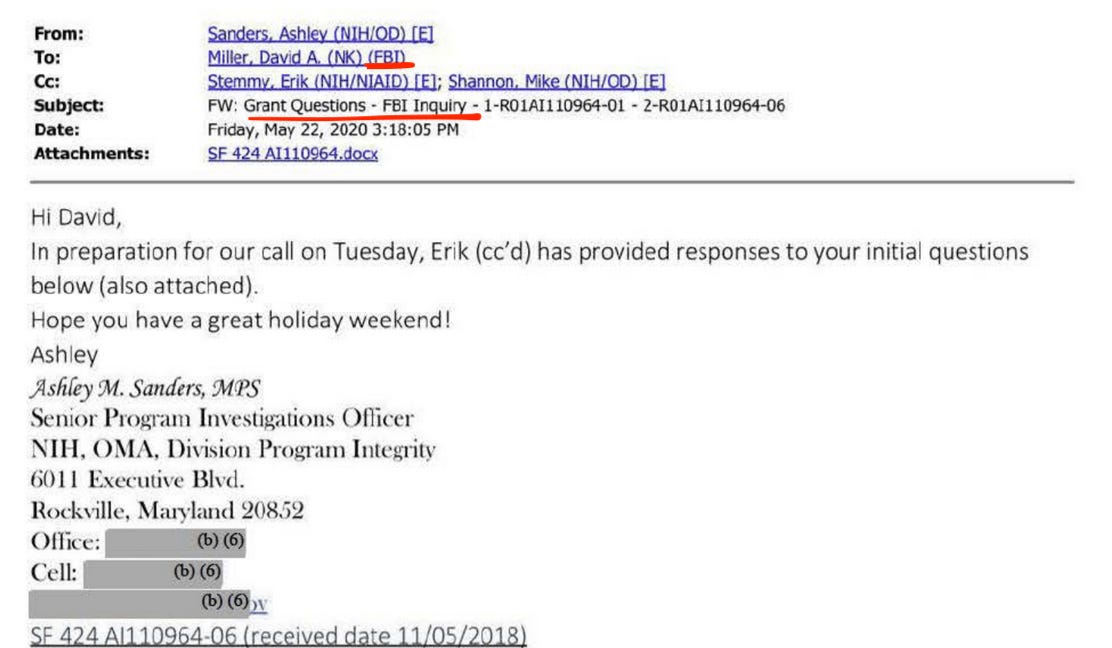

And what none of the media reported at the time is that the FBI was investigating Daszak’s grant throughout the Spring of 2020—the very time period when science writers wrote all these distracting articles.

Like much of the information we now know, this came to light because of documents released through a freedom of information act request, not from science writers rushing to virologists with financial conflicts of interest to get a story comment.

As the New York Times reported in those early days, the 77 Nobel Prize winners demanded of the government:

We ask that you act urgently to conduct and release a thorough review of the actions that led to the decision to terminate the grant, and that, following this review, you take appropriate steps to rectify the injustices that may have been committed in revoking it.

Well, that action seems to have been taken. But the release of a thorough review will have to await further investigation by Congress.