GWPF | 8 Jan 2015

It is perhaps the world’s most famous environmental parable. A settler on Easter Island stood beside the island’s last tree. He or she looked around the treeless horizon, every one of those trees removed by man, and chopped it down anyway. Afterwards, the island died — the nutrients washed away, the landscape stripped. The population collapsed into warfare and cannibalism. It is a compelling tale, but may be completely false, according to research published yesterday. The Easter Island population did collapse, not due to this “ecocide”, but instead something less remarkable: the arrival of Europeans, bringing syphilis, smallpox and slavery. –Tom Whipple, The Times, 7 January 2014

The paper by Benny Peiser tackles head on the evidence Jared Diamond uses to assert that the residents of Easter Island (aka Rapa Nui) committed ecological suicide, or ecocide. According to Peiser, the primary evidence Diamond relies upon are oral traditions from the residents of Rapa Nui and from historical sources, not from the archaeological record. But what is most disturbing is the extent to which Diamond seems determined to avoid looking at the actual genocidal violence of the colonial encounter. –Kerim Friedman, Savage Minds, 11 September 2005

Russil Wvong said: “The journal in which Peiser’s paper was published, Energy & Environment, appears to be a forum for global warming denial; In short, it seems that the global-warming-denial folks have decided to launch an attack on Diamond.” Well, that’s it then. If the people who raise doubts about global warming are also raising doubts about Diamond’s scholarship, we can safely assume that Diamond is correct. No need for evidence at all. –-Savage Minds, 14 September 2005

1) European Disease Led To Demise Of Easter Islanders – The Times, 7 January 2014

2) Benny Peiser: From Genocide to Ecocide – The Rape of Rapa Nui – Energy & Environment, September 2005

It might well have been environmental folly to remove the trees, but, the scientists write in the paper, “the concept of ‘collapse’ is misleading”. “Starvation is not an automatic result of tree removal, and neither is warfare,” said Professor Hamilton. Past research found what appeared to be layers of obsidian spearheads — implying brutal conflict, but further analysis showed they had been used for peeling vegetables. Similarly, while islanders might have lost the ability to go out on the sea to fish, there is evidence that they kept more chickens. It appears that civilisation survived long after the last tree — and collapsed only when the first ship appeared. “Their story is one of ingenuity, resilience, and resourcefulness,” said Professor Hamilton. — Tom Whipple, The Times, 7 January 2014

The ‘decline and fall’ of Easter Island and its alleged self-destruction has become the poster child of a new environmentalist historiography, a school of thought that goes hand-in-hand with predictions of environmental disaster. Why did this exceptional civilisation crumble? What drove its population to extinction? These are some of the key questions Jared Diamond endeavours to answer in his new book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive. According to Diamond, the people of Easter Island destroyed their forest, degraded the island’s topsoil, wiped out their plants and drove their animals to extinction. As a result of this self-inflicted environmental devastation, its complex society collapsed, descending into civil war, cannibalism and self-destruction. While his theory of ecocide has become almost paradigmatic in environmental circles, a dark and gory secret hangs over the premise of Easter Island’s self-destruction: an actual genocide terminated Rapa Nui’s indigenous populace and its culture. –Benny Peiser, Energy & Environment, September 2005

The real mystery of Easter Island is not its collapse. It is why distinguished scientists feel compelled to concoct a story of ecological suicide when the actual perpetrators of the civilisation’s deliberate destruction are well known and were identified long ago. Easter Island is a poor example for a morality tale about environmental degradation. Easter Island’s tragic experience is not a metaphor for the entire Earth. The extreme isolation of Rapa Nui is an exception even among islands, and does not constitute the ordinary problems of the human environment interface. Yet in spite of exceptionally challenging conditions, the indigenous population chose to survive – and they did. What they could not endure, however, and what most of them did not survive, was something altogether different: the systematic destruction of their society, their people and their culture. –Benny Peiser, Energy & Environment, September 2005

Hunt and Lipo, relying partly on a paper by Peiser (written apparently without first-hand experience of Easter Island), claimed that Easter’s collapse was due to European impact, and that the islanders were coping successfully before European arrival. No one disputes that European impact did devastate what was left of indigenous Easter society, especially by introduced diseases and by a slave raid. However, to blame it all on Europeans dismisses all the convincing evidence that Easter society had been collapsing well before European arrival: evidence such as the near-completion of deforestation (attested by the disappearance of forest pollen and of forest plant remains), the evidence of widespread warfare (from detailed oral accounts and preserved weapons and skeletal injuries), the cessation of carving statues, the disappearance of oceanic fish and mammals from the diet (because of no trees to build canoes to harpoon them), and the desperate resort to sugarcane scraps for fuel (because of disappearance of native plant fuel). These and other types of evidence that have built up our current understanding of Easter Island history are denied. –-Jared Diamond, 22 September 2011

1) European Disease Led To Demise Of Easter Islanders

The Times, 7 January 2014

Tom Whipple

It appears that civilisation on Easter Island collapsed only when the first ship appeared

It is a compelling tale, but may be completely false, according to research published yesterday. The Easter Island population did collapse, not due to this “ecocide”, but instead something less remarkable: the arrival of Europeans, bringing syphilis, smallpox and slavery.

A study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences has dated the tools used by the islanders, made from obsidian rock and scattered around the island, and found that they reveal a pattern of farming and land use at odds with the idea that the civilisation caused its own downfall.

Instead of a sudden agricultural collapse associated with deforestation, the scientists from Virginia Commonwealth University discovered from dating the tools that there was a gradual decline in some areas — but not others. It seems they survived perfectly well after the last tree was cut down.

For the Rapa Nui, the indigenous name for the islanders, it is welcome news. The collapse narrative has in recent years become a compelling metaphor in parts of the environmental community for the way humanity is treating its planet today, but the Rapa Nui have never been ecstatic about being used as an exemplar of man’s stupidity. Especially by people whose own ancestors gave theirs smallpox.

“It is a terrible presumption to say there was a food shortage,” said Professor Sue Hamilton, an Easter Island expert from UCL who was not directly involved in the research. “Yes, if you take away trees you expose the soil to having its nutrients flushed away, but you can do other things.”

Rather than looking just at the stone statues, called moai, which did stop being made with the last tree, she and other archaeologists have tried to interpret the entire landscape. They have found that the Rapa Nui came up with clever solutions to the lack of trees — in particular “rock mulching” where they put rocks across the soil to hold in nutrients.

It might well have been environmental folly to remove the trees, but, the scientists write in the paper, “the concept of ‘collapse’ is misleading”.

“Starvation is not an automatic result of tree removal, and neither is warfare,” said Professor Hamilton. Past research found what appeared to be layers of obsidian spearheads — implying brutal conflict, but further analysis showed they had been used for peeling vegetables.

Similarly, while islanders might have lost the ability to go out on the sea to fish, there is evidence that they kept more chickens. It appears that civilisation survived long after the last tree — and collapsed only when the first ship appeared.

“Their story is one of ingenuity, resilience, and resourcefulness,” said Professor Hamilton.

2) Benny Peiser: From Genocide to Ecocide – The Rape of Rapa Nui

Energy & Environment, September 2005

Benny Peiser

ABSTRACT

The ‘decline and fall’ of Easter Island and its alleged self-destruction has become the poster child of a new environmentalist historiography, a school of thought that goes hand-in-hand with predictions of environmental disaster. Why did this exceptional civilisation crumble? What drove its population to extinction? These are some of the key questions Jared Diamond endeavours to answer in his new book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive. According to Diamond, the people of Easter Island destroyed their forest, degraded the island’s topsoil,

wiped out their plants and drove their animals to extinction. As a result of this self-inflicted environmental devastation, its complex society collapsed, descending into civil war, cannibalism and self-destruction. While his theory of ecocide has become almost paradigmatic in environmental circles, a dark and gory secret hangs over the premise of Easter Island’s self-destruction: an actual genocide terminated Rapa Nui’s indigenous populace and its culture. Diamond, however, ignores and fails to address the true reasons behind Rapa Nui’s collapse. Why has he turned the victims of cultural and physical extermination into the perpetrators of their own demise? This paper is a first attempt to address this disquieting quandary. It describes the foundation of Diamond’s environmental revisionism and explains why it does not hold up to scientific scrutiny.

INTRODUCTION

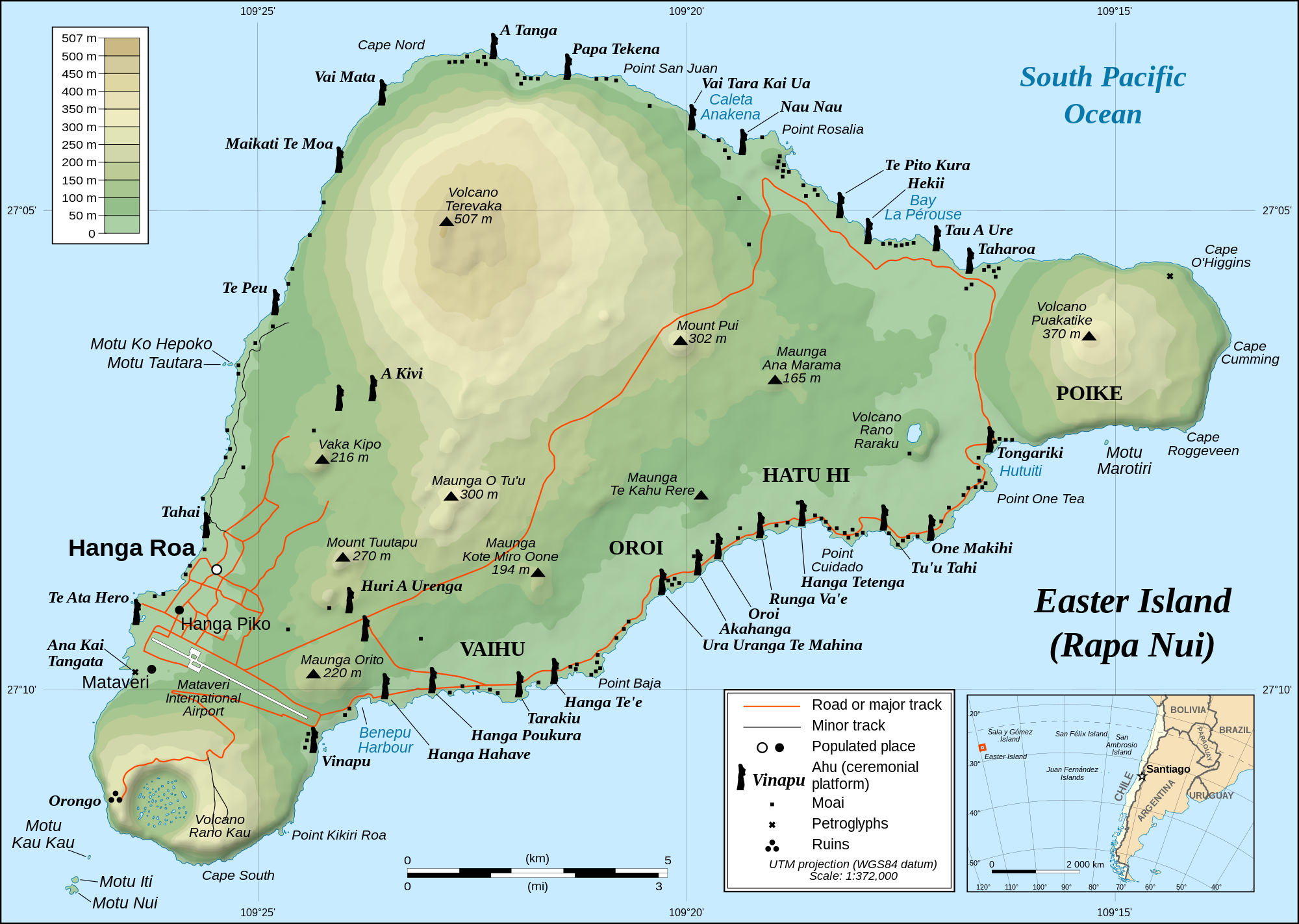

Of all the vanished civilisations, no other has evoked as much bafflement, incredulity and conjecture as the Pacific island of Rapa Nui (Easter Island). This tiny patch of land was discovered by European explorers more than three hundred years ago amidst the vast space that is the South Pacific Ocean. Its civilisation attained a level of social complexity that gave rise to one of the most advanced cultures and technological feats of Neolithic societies anywhere in the world. Easter Island’s stone-working skills and proficiency were far superior to any other Polynesian culture, as was its unique writing system. This most extraordinary society developed, flourished and persisted for perhaps more than one thousand years – before it collapsed and became all but extinct.

Why did this exceptional civilisation crumble? What drove its population to extinction? These are some of the key questions Jared Diamond endeavours to answer in his new book Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail or Survive (Diamond, 2005) in a chapter which focuses on Easter Island.

Diamond’s saga of the decline and fall of Easter Island is straightforward and can be summarised in a few words: Within a few centuries after the island was settled, the people of Easter Island destroyed their forest, degraded the island’s topsoil, wiped out their plants and drove their animals to extinction. As a result of this self-inflicted environmental devastation, its complex society collapsed, descending into civil war, cannibalism and self-destruction. When Europeans discovered the island in the 18th century, they found a crashed society and a deprived population of survivors who subsisted among the ruins of a once vibrant civilisation.

Diamond’s key line of reasoning is not difficult to grasp: Easter Island’s cultural decline and collapse occurred before Europeans set foot on its shores. He spells out in no uncertain terms that the island’s downfall was entirely self-inflicted: “It was the islanders themselves who had destroyed their own ancestor’s work” (Diamond, 2005).

Lord May, the President of Britain’s Royal Society, recently condensed Diamond’s theory of environmental suicide in this way: “In a lecture at the Royal Society last week, Jared Diamond drew attention to populations, such as those on Easter Island, who denied they were having a catastrophic impact on the environment and were eventually wiped out, a phenomenon he called ‘ecocide’” (May, 2005).

Diamond’s theory has been around since the early 1980s. Since then, it has reached a mass audience due to a number of popular books and Diamond’s own publications. As a result, the notion of ecological suicide has become the “orthodox model” of Easter Island’s demise. “This story of self-induced eco-disaster and consequent self-destruction of a Polynesian island society continues to provide the easy and uncomplicated shorthand for explaining the so-called cultural devolution of Rapa Nui society” (Rainbird, 2002).

The ‘decline and fall’ of Easter Island and its alleged self-destruction has become the poster child of the new environmentalist historiography, a school of thought that goes hand-in-hand with predictions of environmental disaster. Clive Ponting’s The Green History of the World – for many years the main manifest of British eco-pessimism – begins his saga of ecological destruction and social degeneration with “The Lessons of Easter Island” (Ponting, 1992:1ff.).

Others view Easter Island as a microcosm of planet Earth and consider the former’s bleak fate as symptomatic for what awaits the whole of humanity. Thus, the story of Easter Island’s environmental suicide has become the prime case for the gloomiest of grim eco-pessimism. After more than 30 years of palaeo-environmental research on Easter Island, one of its leading experts comes to an extremely gloomy conclusion: “It seems […] that ecological sustainability may be an impossible dream. The revised Club of Rome predictions show that it is not very likely that we can put of the crunch by more than a few decades. Most of their models still show economic decline by AD 2100. Easter Island still seems to be a plausible model for Earth Island.” (Flenley, 1998:127).

From a political and psychological point of view, this imagery of a complex civilisation self-destructing is overwhelming. It portrays an impression of utter failure that elicits shock and trepidation. It is in form of a shock-tactic when Diamond employs Rapa Nui’s tragic end as a dire warning and a moral lesson for humanity today: “Easter [Island’s] isolation makes it the clearest example of a society that destroyed itself by overexploiting its own resources. Those are the reasons why people see the collapse of Easter Island society as a metaphor, a worst-case scenario, for what may lie ahead of us in our own future” (Diamond, 2005).

While the theory of ecocide has become almost paradigmatic in environmental circles, a dark and gory secret hangs over the premise of Easter Island’s self-destruction: an actual genocide terminated Rapa Nui’s indigenous populace and its culture. Diamond ignores, or neglects to address the true reasons behind Rapa Nui’s collapse. Other researchers have no doubt that its people, their culture and its environment were destroyed to all intents and purposes by European slave-traders, whalers and colonists – and not by themselves! After all, the cruelty and systematic kidnapping by European slave-merchants, the near-extermination of the Island’s indigenous population and the deliberate destruction of the island’s environment has been regarded as “one of the most hideous atrocities committed by white men in the South Seas” (Métraux, 1957:38), “perhaps the most dreadful piece of genocide in Polynesian history” (Bellwood, 1978:363).

So why does Diamond maintain that Easter Island’s celebrated culture, famous for its sophisticated architecture and giant stone statues, committed its own environmental suicide? How did the once well-known accounts about the “fatal impact” (Moorehead, 1966) of European disease, slavery and genocide – “the catastrophe that wiped out Easter Island’s civilisation” (Métraux, ibid.) – turn into a contemporary parable of self-inflicted ecocide? In short, why have the victims of cultural and physical extermination been turned into the perpetrators of their own demise?

This paper is a first attempt to address this disquieting quandary. It describes the foundation of Diamond’s environmental revisionism and explains why it does not hold up to scientific scrutiny.