NZCPR | 6 March 2015

Welfare and the state have replaced husbands and marriage

During an open debate at the United Nations Security Council in New York last week – to mark its 70th anniversary – Foreign Affairs Minister Murray McCully launched a stinging attack, calling the fifteen member council “impotent” and urging it to lift its game. New Zealand’s two year term on the Council, which has just commenced, was gained through the backing of many other UN nations that would like to see reform.

In his address, Mr McCully explained that a greater focus was needed on conflict-prevention: “It is time for us to confront the root causes that have seen this council avoid the challenging task of conflict-prevention simply because the politics and the diplomacy have been too difficult.” While the UN has a peacekeeping budget of over US$8 billion which funds over 120,000 personnel, virtually no investment is made into preventing situations from escalating into conflict.

Mr McCully stated that the future credibility of the Security Council depends on satisfactorily resolving the abuse of the veto power by the Council’s five permanent members – France, Britain, the United States, China and Russia: “The use of the veto or the threat of the veto is the single largest cause of the UN Security Council being rendered impotent in the face of too many serious international conflicts.” He wants all permanent members to follow the lead of France and make a commitment to voluntarily retire their veto in cases of mass atrocity – an understanding that existed when these nations first gained their veto rights in 1945.

The veto right of the Security Council’s five permanent members was also an issue raised by Amnesty International in its annual report released last week. The 415 page review of the state of human rights in 160 countries singled out the Security Council for harsh criticism saying that the five permanent members had abused their veto right by promoting political or geo-political self-interest above the protection of civilians. The report went on to claim that the global response to the atrocities being carried out by groups like the Islamic State against civilians has been shameful and ineffective.

Amnesty International, a leading global human rights advocate with seven million supporters and an annual budget of over $100 million, was founded in 1961 by British lawyer Peter Benenson. Concerned by the plight of freedom fighters imprisoned in foreign countries, Amnesty focussed on prisoners of conscience, defined as, “Any person who is physically restrained (by imprisonment or otherwise) from expressing (in any form of words or symbols) any opinion which he honestly holds and which does not advocate or condone personal violence.”

The organisation drew attention to the plight of such prisoners – using mass media campaigns and reports on the policies and practices of offending governments – in order to ensure public pressure was directed towards those who could influence their release.

As Amnesty International became more successful, the pressure of a growing support base and the need to raise money to fund their increasingly bureaucratic organisational structure led to a broadening of their mandate to include the full spectrum of human rights. Some would say this resulted in a loss of competency and focus. Instead of solely raising awareness of prisoners’ rights in dictatorial regimes, Amnesty now campaigns on such populist issues as globalisation, capitalism, poverty, and gay rights.

According to their website, the charity’s priorities for 2010 – 2016 are “empowering people living in poverty, defending unprotected people on the move, defending people from violence by state and non-state actors, and protecting people’s freedom of expression and freedom from discrimination”.

One of Amnesty’s most prominent critics is a former board member, Dr. Francis Boyle, professor of International Law at the University of Illinois-Champaign, who explains, “Amnesty International is primarily motivated not by human rights but by publicity. Second comes money. Third comes getting more members. Fourth, internal turf battles. And then finally, human rights, genuine human rights concerns.”

As a result of their change of focus, Amnesty International has now become highly critical of free democratic nations, instead of maintaining a single-minded focus on the grave human rights abuses in authoritarian regimes. Not only does this discredit the organisation and devalue its impact, but it means that it is failing the real victims of human rights abuses world-wide.

Amnesty’s criticism of New Zealand’s so-called human rights violations, as listed in their annual report, illustrates the point.

For instance, Amnesty makes some highly critical generalised comments about governments that are not doing enough to protect citizens from the threat of terrorism, but when our government passed legislation to increase national security and reduce the threat of terrorism, they disapproved. In particular, they were critical of the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB) legislation and the Countering Terrorist Fighters Legislation.

In terms of the legislation surrounding New Zealand’s lead intelligence agency, the GCSB, the new law was required because the original law, which had been passed by the previous Labour Government in 2003, had been found to be lacking in clarity and oversight. Given the crucial role that intelligence agencies play in keeping citizens safe, crippling the GCSB through unworkable legislation was simply not an option.

Amnesty also criticised the government over the foreign fighter law to counter terrorism, claiming it would restrict rights to privacy and the freedom of movement. And it is certainly designed to do just that for potential terrorists!

The Countering Terrorist Fighters Legislation Bill, which was passed by a substantial majority of the House, gives greater powers to the Security Intelligence Service for surveillance and to the Minister of Internal Affairs for suspending and cancelling passports. The new law also fulfils our international obligation to comply with a recent United Nations Security Council resolution urging States to restrict the movements of people travelling to become foreign terrorist fighters. At the time, Government agencies had identified 30 to 40 people of concern, with another 30 to 40 requiring further investigation.

Amnesty also complained about the time frame for consultation over the new law, but following an increased terrorist threat in Australia, as soon as the new government was sworn in after the 2014 General Election, work began on the Bill. It was introduced under urgency at the end of November so it could be passed before the long Christmas break. While submissions on the Bill were only open for two days, around 600 were received, and all of the submitters who wanted to appear before the committee were heard over a three day period.

In addition, the Bill contains a sunset clause, expiring on 1 April 2018, since the new GCSB legislation introduced a comprehensive review process for all security and intelligence laws and agencies: “A review of the intelligence and security agencies, the legislation governing them, and their oversight legislation must, be commenced before 30 June 2015; and afterwards, held at intervals not shorter than 5 years and not longer than 7 years.”

When it comes to legal protection in law for human rights in New Zealand, the Amnesty International report claims a “lack of human rights oversight in parliamentary processes”. Yet the 1990 New Zealand Bill of Rights Act has within it a requirement for the Attorney-General to alert Parliament to any draft legislation that appears to be inconsistent with human rights obligations.

In terms of women’s and children’s rights, the Amnesty report is highly critical, claiming that “27 percent of New Zealand children remained in poverty. Maori and Pacific Island children were disproportionately represented in child poverty statistics, highlighting systemic discrimination”.

This week’s NZCPR Guest Commentator Lindsay Mitchell has looked at the Amnesty report and disputes their findings, noting that, rather than discriminating against Maori andPacific Island families and children, if anything, our New Zealand health and education systems provide them with additional benefits. So what about the welfare system?

“Are Maori and Pacific Island children being denied benefits that NZ European children access? Again, the opposite is nearer the truth. Maori children, in particular, disproportionately receive social assistance, especially by way of Sole Parent Support.

“A recent New Zealand Statistics report into the employment rates of NZ females reveals that 40 percent of Maori mothers, and 29 percent of Pacific Island mothers are un-partnered. This has a direct bearing on child poverty.

“The official source of child poverty statistics is the Household Incomes Report published by the Ministry of Social Development. It finds: …the poverty rate for children in sole-parent families living on their own is high at 60%…the poverty rate for children in two-parent families is much lower at 14%…”

Lindsay asks whether there may perhaps be some systemic discriminatory force that prevents Maori and Pacific Island parents from forming stable partnerships and concludes: “There is validity to the theory that welfare benefits have undermined marriage. If the state is prepared to financially replace fathers, especially low income fathers, then there will be inevitable repercussions”.

The reality is that the sole parent benefit has indeed significantly undermined the Maori family. But it is not because of discrimination – it is a behavioural problem: disproportionately more Maori women than non-Maori women regard state support and sole parenthood as a viable lifestyle option.

Without a doubt, the poorest families in New Zealand are single parent families on benefits. But a few extra dollars of benefit each week will not cure welfare poverty. The only cure is a job.

Just last week in Parliament, the Minister of Social Development explained that “nine out of 10 young people who went on to a benefit grew up in benefit-dependent homes as children”. This reinforces the importance of breaking the cycle of intergenerational welfare dependency, and in particular, eliminating the financial incentives within the benefit system that encourage the creation of sole parent families.

In essence, New Zealand’s thirty year experiment with the social engineering of families by the state has not only failed dismally, but by removing fathers from homes and creating sole parent welfare dependency on a massive scale, endless children have been seriously damaged. The consequences are clear to see.

As the Amnesty report outlines, “Maori made up 50% of the total prison population and 65% of the female prison population, despite being only 15% of the general population”. But it isn’t because of discrimination – the root cause is the breakdown of family. As the late Celia Lashlie, a former prison manager, used to say, just ask any prisoner about their family upbringing. Most have been raised without fathers in sole parent families. Many grew up in unstable and violent homes, and lacking proper nurturing, socialisation and supervision, eventually found themselves on the path to criminal offending.

With the stand-alone sole parent benefit creating such a strong incentive for single parenthood amongst young women, changing the system to one that provides support based on work – as recommended by the Welfare Working Group – is the only way that the situation will be permanently improved.

If Amnesty International were to recommend that, as the way to reduce child poverty amongst Maori – and criminal offending – then their credibility might well improve!

Show us the “systematic discrimination”

A recent Amnesty International report made the following observation about New Zealand:

The 2013 Technical report on Child Poverty found that 27% of New Zealand children remained in poverty. Maori and Pacific island children were disproportionately represented in child poverty statistics, highlighting systemic discrimination.

Really? Which system is discriminating against Maori andPacific Island children?

With free GP visits and prescriptions – recently extended to all under 13′s – it’s not the health system. With community service cards and medical centres like the Petone Union Health Centre which provides “comprehensive primary health services to Maori, Pacific, Refugee and low income families” free to patients 18 and under, the case could be made that Maori and Pacific Island children are the subject of positive discrimination though that is unlikely what Amnesty International intended. Immunisation rates are steadily increasing (PI rates are now higher than NZ European). School nurses are a feature in low decile schools and of course, whanau ora services are specifically aimed at improving the health of Maori families. Oral health services are free to all children and adolescents. Maternity services are targeted at low income vulnerable mothers-to-be dominated by Maori and Pacific Island females.

Is it the education system they refer to? The targeted funding to low decile schools is well-known. Charter schools are being established in some of the poorest neighbourhoods to meet the challenge of the under-achieving tail. Free hours of early childhood education have been steadily expanded. Again a case could be made for positive discrimination as opposed to negative.

Perhaps Amnesty International meant that the labour market discriminates against Maori and Pacific Island and, by proxy, their children. Yet it is unavoidable that low or no educational qualifications will predict future employability. Which takes us back to the education system that, as alluded to earlier, has, for the most recent decades, operated in a manner that exercises positive rather than negative discrimination towards ethnic minorities. Targeted funding of low income schools is synonymous with targeted funding of Maori and Pasifika.

Is the social assistance system stacked against them? Are Maori and Pacific Island children being denied benefits that NZ European children access? Again, the opposite is nearer the truth. Maori children, in particular, disproportionately receive social assistance, especially by way of Sole Parent Support.

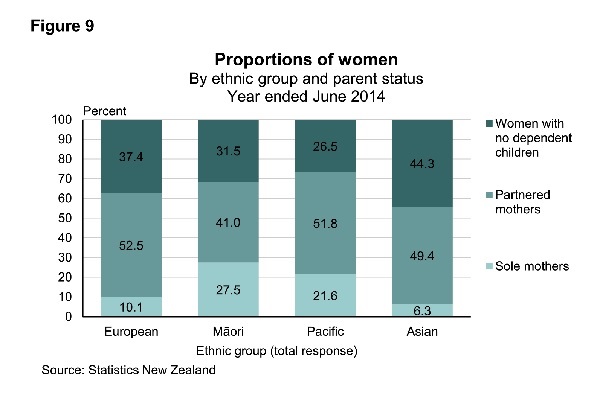

A recent New Zealand Statistics report into the employment rates of NZ females featured the following graph:

It reveals that 40 percent of Maori mothers, and 29 percent of Pacific Island mothers are unpartnered. This has a direct bearing on child poverty.

The official source of child poverty statistics is the Household Incomes Report published by the Ministry of Social Development. It finds:

…the poverty rate for children in sole-parent families living on their own is high at 60%…the poverty rate for children in two-parent families is much lower at 14%…

Is there some systemic discriminatory force that prevents Maori and Pacific Island parents from forming stable partnerships?

I don’t know what it is.

There is validity to the theory that welfare benefits have undermined marriage. If the state is prepared to financially replace fathers, especially low income fathers, then there will be inevitable repercussions. When the universal, non-means-tested family benefit – paid directly to mothers – was introduced in the 1940s, Maori marriage rates climbed. Only married mothers qualified to receive them.

In The New Zealand family from 1946, Treasury comments:

Legal marriage is now less common among Maori than among non-Maori …The estimates for people aged 60 and over are, however, an exception. Maori in this age group—who would have been entering the main marriage ages during the baby boom—appear to have just as high a probability of ever marrying as other New Zealanders of the same age. Maori in earlier periods had not seen any great need to ask non-Maori officials to provide legal sanction for their marriages (Pool 1991: 109) so the baby boom may well have been the high water mark for legal marriage among Maori.

After the 1973 Domestic Purposes Benefit (DPB) guaranteed eligibility to a relatively generous benefits for single parents regardless of the reason for their circumstance, the Maori marriage rate plummeted.

Welfare had a more devastating effect on Maori families because their incomes were lower and Maori men couldn’t compete with the DPB as easily. Pacific Island families have withstood the sole- parent- subsidisation assault better due to other cultural and Christian traditions which uphold and protect marriage and intact families. Even Pacific Island single mums are more likely to reside with their extended family.

But again, the welfare system didn’t discriminate against Maori and Pacific Island children. It sought to relieve their poverty by replacing incomes lost to unemployment or a missing partner. That it achieved the opposite – grew the incidence of relative poverty – is an appalling result.

Amnesty International makes pronouncements about every country in the world (in this particular report, 160 countries) but cannot intimately understand the development of child poverty locally. The only purpose this report serves is to provide headline fodder for the political Left.

Consequently this sort of claim soon has the silent majority’s eyes glazing over. It reads like a statement about minority rights in the 1930s or earlier. It doesn’t reflect the reality of New Zealand in 2015.