SAGE HANA | 14 Dec 2023

Good Club gonna good

One guy is a Big Tech One ID Surveillance helpful inventor. Came up the ranks with DARPA as a kid and went on to become a quarter billionaire and Democratic Party Megadonor.

When Covid “emerged” he was involved with a Rockefeller Philanthropy administered fund that studied Remdesivir.

Sage’s Newsletter is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.Subscribe

He is concerned about overpopulation.

The other guy is a lifetime biowarfare industries medical countermeasures scientist.

When Covid hit, he was involved with a Defense Threat Reduction Agency project that was designed to identify medical countermeasures for a novel entity, say a novel coronavirus. That project came up with Remdesivir.

He is also concerned with overpopulation.

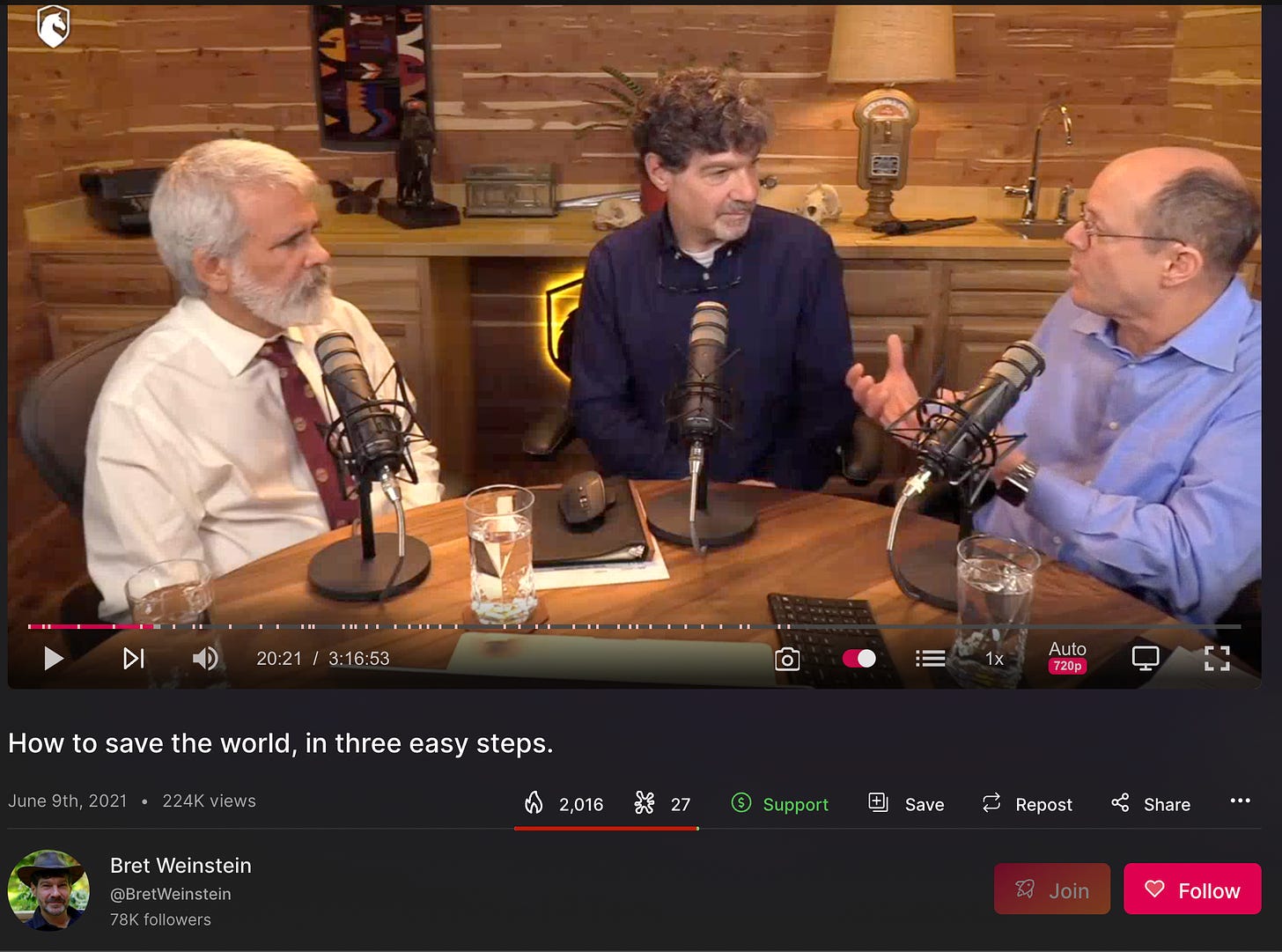

These two guys found themselves on a podcast about How to Save the World from the coronavirus pandemic with another guy whose brother was the consigliere for another billionaire. Other billionaire runs a CIA data mining site.

Ladies and gentleman, the Vaccine Freedom Movement!

Receipts.

Guy #1.

Little Stevie and DARPA

·

15 MAY

Computer centers were intimidating places in 1969. Machines were huge, locked in air-conditioned rooms, and fed with punched cards. Time on them did not come cheaply and was tightly rationed. And the computer room in Boelter Hall at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), was no exception.

In one corner of the room sat a state-of-the-art Scientific Data Systems Sigma 7 computer. Off limits to the countless engineering students, it was reserved for a small group of researchers funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) and busy inventing the technology that would evolve into the Internet.

Among those researchers was Vinton Cerf, now senior vice president of Internet architecture and technology at Worldcom Inc., Ashburn, Va. One evening, he was sitting next to the Sigma 7 doing some programming when a scruffy 12-year-old with a piping voice interrupted him with a question, then asked another, and another. The kid was Steve Kirsch–or little Stevie, as he came to be known around UCLA.

“He must have grabbed the door when someone walked out of the room,” Cerf said. The door was usually locked. “I didn’t want to be bothered at first.”

But something about Kirsch reminded Cerf of himself at that age. “A part of me said, ‘Be nice to the kid, you can’t buy enthusiasm’.” So Cerf and his colleagues set up Kirsch with a computer account.

Promo Code Outraged Human

Kirsch profiled in Forbes, July, 2020, one year prior to Dark Horse

Silicon Valley entrepreneur and computer whiz Steve Kirsch is no stranger to tackling tall challenges with creative solutions. Fascinated with computers from a young age, he has been in the CS and engineering game for over 50 years. Over the course of his career, he has founded more than seven companies, including Propel Software, Mouse Systems Corporation, Frame Technology Corporation, and Infoseek – all dedicated to improving computer software and tech.

He’s equally known for his philanthropic work across a wide variety of environmental, medical, local and planet-safety causes – so prolific that Hillary Clinton presented him with a National Caring Award in 2003.

When COVID-19 struck earlier this year, Steve recognized both his disadvantages as an immunocompromised man and his opportunity to make a difference as a man of means. He had already seen the efficacy and the practicality of using preexisting drugs and applying them toward other maladies, and so founded the COVID-19 Early Treatment Fund (CETF) – the only organization in the world focused on finding the most promising drugs and treatments that, when given sufficiently early, can reduce hospitalization and death rates.

“I started looking for opportunities to apply my expertise in a field where it was needed, where other people weren’t covering it,” he explained. “World leaders have promised nothing for outpatient trials, and the short-term way to attack a virus is to discover a drug or drugs that are already on the shelf today.”

The organization supports grantees through funding, improving study protocols, advertising trials through op-eds, newspaper and TV interviews, and finding ways to manufacture drugs faster and at lower cost. The fund is managed by Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, which will disburse grants that are recommended – in coordination with research being undertaken – by CETF’s Scientific Advisory Board. The initiative has drawn grant proposals from top scientists, including cancer genomics pioneer Bert Vogelstein and Michel Nussenzweig, whose research has led to the development of innovative vaccines against infectious disease and new treatments for autoimmunity.

Currently, the goal is to raise $30 million to continue supporting scientists developing preventative medicines – and the approach is paying off.

Thus far, CETF has raised funding for clinical trials for drug candidates including Peginterferon lambda, a hepatitis D treatment, and Camostat mesylate, a protease inhibitor used to treat reflux esophagitis and chronic pancreatitis. The organization is also raising funds to support COVID-related trials of remdesivir, a broad-spectrum antiviral developed by Gilead Sciences, and Toyama Chemical’s favipiravir, an antiviral medication currently used to treat influenza in Japan.

“Like investors, you don’t want to invest in just one stock,” says Kirsch. “We’re just identifying where the best work is to fund, looking for the best opportunities that can make the difference on lowering the hospitalization rates and lowering the fatality rates. Because if we can move the needle on those, that’s huge.

If you can spend $20 million and test every drug scientists think are worth testing, those are the first philanthropic dollars that should be spent.”

To get involved, visit the link below, where supporters can give funds via credit card or wire transfer, or via donor-advised fund (DAF).

COVID-19 EARLY TREATMENT FUNDMake a donation – COVID-19 Early Treatment Fund

Kirsch warns of hooooman extinction due to climate change on his blog in 2010.

Here are the details…

Ostensibly, we will die due to the effects of global warming. By 2100, according to the IPCC consensus report (see Table SPM.3 on page 13 and footnote 5 on page 2 which explains the ranges in the table), there is a 5% chance that the average temperature of the planet will rise by more than 6.4ºC. That’s in the report, clear as day, but nobody talks about it because only a few people understand exactly what that means to our planet. But one guy from the UK (who has hardly gotten any press in the US) Mark Lynas, has done the research on what this means. Lynas spent 3 years of his life poring over 10,000 scientific papers and found that, although it doesn’t sound like a lot, a 6ºC temperature rise will pretty much wipe out just about every life form on the planet, us included. Although IPCC scientists had previously projected that there was only a 5% chance of more than a 6.4ºC warming by 2100, the assumptions on which those projections are based have already been exceeded, which is pointed out in this paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The paper points out that the assumptions in all 6 emission scenarios considered by the IPCC have already been exceeded. So that’s why I am using the numbers from the A1FI scenario, which gave a 5% chance of exceeding 6.4ºC by 2100. If it doesn’t happen by 2100, it will not be long after. I wrote a short web page “Why global warming should be every candidate’s #1 priority” describing this in detail.

The bottom line is this: unless we change our ways, there is more than a 5% chance of a mass human extinction in less than 100 years. I’m just telling you what the overwhelming scientific consensus is. Whether or not you choose to believe it is, of course, up to you. If you do disagree, what is the scientific basis for your disagreement? Do you know something the scientists don’t?

If we are going to save humanity from extinction, we had better be doing something about these 3 issues:

- global warming

- overpopulation

- the accelerating decline of every single major ecosystem

All of these trends are getting worse. None have been reversed at a global scale. We need action on all three. But right now, none of the candidates have the courage to even talk about serious solutions. In fact, on some issues, they won’t even talk about the problem!

The Other Guy.

Defense Threat Reduction Agency

FORT BELVOIR, Va. – The COVID pandemic took the world by surprise. Researchers were left scrambling to devise a way to best mitigate the negative impact this disease has on global health. However, at the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) it is common to operate in the “what if” space when it comes to potential biological threats. In fact, DTRA investments in technologies that detect, mitigate, or neutralize chemical and biological threats to the military and the nation date back more than 20 years.

“In late 2019, DTRA started a new program called Discovery of Medical Countermeasures Against Novel Entities (DOMANE) to address novel and emerging threats,” stated Dr. David Hone, Chief Scientist within the Vaccines and Therapeutics Division at DTRA. “Based on previous work, we decided DOMANE would not only focus on FDA-approved drugs but also combination therapeutics, as we believe that no single drug will be completely effective in treating new diseases. COVID-19 has provided us an opportunity to test our hypotheses using DOMANE.”

DOMANE provides rapid decision-making capabilities to identify FDA-approved drugs that will most likely be effective therapeutics for COVID-19. Repurposing candidate drugs from a pool about 7,500 FDA-approved drugs to advance an effective COVID-19 therapeutic allows for a more rapid response in developing a therapeutic regimen. The end-result is a response that modifies COVID-19 in treated patients and promotes a speedy recovery.

Veklury®, which is more commonly referred to as Remdesivir, is a ribonuclease inhibitor developed by Gilead Sciences. It delivers broad-spectrum antiviral activity and has proven to be a modestly effective therapeutic for the treatment of COVID-19. Originally developed as an Ebola Zaire countermeasure, this DTRA-funded inhibitor transitioned for more advanced testing due to promising pre-clinical trials. Remdesivir inhibits viral replication in a wide variety of pathogens and was one of the first therapeutics identified in the Defense Department for repurposing to treat COVID-19. In the summer of 2020, Remdesivir received authorization for emergency use only in COVID-19 patients with continued FDA oversight.

Are you clocking this? “DTRA-funded inhibitor”?

Also, again for emphasis:

Remdesivir inhibits viral replication in a wide variety of pathogens and was one of the first therapeutics identified in the Defense Department for repurposing to treat COVID-19.

It would be interesting to get a glimpse behind the curtain, would it not?

Simultaneously in the U.S., it is claimed, an old colleague of Callahan’s Dr. Robert Malone had been conducting a study with U.S. government-sponsored research teams. Specifically, Malone was working alongside U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) consultants to carry out supercomputer-based analyses to identify existing FDA-approved drugs that may be useful against the novel coronavirus responsible for COVID-19. Per their analyses, famotidine turned out to be the “most attractive combination of safety, cost and pharmaceutical characteristics“.

Bob’s CV, 2021.

Another project he has been involved with is a DTRA/DOMANE-funded development and performance of a virtual outpatient clinical trial designed to test new monitoring and data capture technology while using COVID19 as a live-fire example. He has helped open two IND for famotidine and celecoxib use for treatment and prevention of COVID19 disease including an associated

1

Robert W. Malone, MD, MS

drug master file, and has enabled teaming/pharmaceutical supply arrangements with two major pharmaceutical firms.

Is there anybody on the Freedom Team who is not trying to save the world from too many critters?

I think Steve Kirsch’s blogpost is from 2010.

He references extinction within 90-years, and says 2100 in the post.

In 2009, the Good Club meetings happened.

They’re called the Good Club – and they want to save the world

This article is more than 14 years old

Paul Harris in New York reports on the small, elite group of billionaire philanthropists who met recently to discuss solving the planet’s problems

It is the most elite club in the world. Ordinary people need not apply. Indeed there is no way to ask to join. You simply have to be very, very rich and very, very generous. On a global scale.

This is the Good Club, the name given to the tiny global elite of billionaire philanthropists who recently held their first and highly secretive meeting in the heart of New York City.

The names of some of the members are familiar figures: Bill Gates, George Soros, Warren Buffett, Oprah Winfrey, David Rockefeller and Ted Turner. But there are others, too, like business giants Eli and Edythe Broad, who are equally wealthy but less well known. All told, its members are worth $125bn.

The meeting – called by Gates, Buffett and Rockefeller – was held in response to the global economic downturn and the numerous health and environmental crises that are plaguing the globe. It was, in some ways, a summit to save the world.

No wonder that when news of the secret meeting leaked, via the seemingly unusual source of an Irish-American website, it sent shock waves through the worlds of philanthropy, development aid and even diplomacy. “It is really unprecedented. It is the first time a group of donors of this level of wealth has met like that behind closed doors in what is in essence a billionaires’ club,” said Ian Wilhelm, senior writer at the Chronicle of Philanthropy magazine.

The existence of the Good Club has struck many as a two-edged sword. On one hand, they represent a new golden age of philanthropy, harking back to the early 20th century when the likes of Rockefeller, Vanderbilt and Carnegie became famous for their good works. Yet the reach and power of the Good Club are truly new. Its members control vast wealth – and with that wealth comes huge power that could reshape nations according to their will. Few doubt the good intentions of Gates and Winfrey and their kind. They have already improved the lives of millions of poor people across the developing world. But can the richest people on earth actually save the planet?

Also in 2010, the Rockefellers planned Operation Lockstep.

Operation Lockstep, the 2010 Rockefeller Philanthropath Plan to Subjugate the World

·

4 MAR

In 2010, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Rockefeller Foundation, one of Our major “philanthropic” organs, convened what is called a “scenario planning exercise” where future events that we may or may not be planning are “gamed”.

Ostensibly, future and scenario planning is simply prudent, especially as regards public health, so it was not seen as any threat by the masses at large. Nevertheless, Our corollary organs did everything possible to keep this information from them, including high levels of increasing and creeping censorship, especially where health information is concerned.

The exercise was conducted in association with a group called the Global Business Network (GBN), a now-defunct group of very sophisticated and connected Silicon Valley influence peddlers described by Wikipedia as a “global strategy firm that specialized in helping organizations [including businesses, NGOs and governments] to adapt and grow in an increasingly uncertain and volatile world.”

These included “futurist” Peter Schwartz, Stewart Brand, both former members of Students for a Democratic Society, and Jay Ogilvy, an Esalen Institute–associated Statfor board member who has no Wikipedia page but whose family name is the same as one of the biggest names in advertising. (It is unclear if there is a connection.)

All are connected to SRI International, formerly Stanford Research International, and Royal Dutch/Shell. Stanford University’s science departments are well known to be connected with DARPA and US intelligence, and are creators of so-called “artificial intelligence”.

The Narrative: “Lock Step”

The “Lock Step” scenario is the first of four narratives presented in the Rockefeller Foundation’s summary document, “Scenarios for the Future of Technology and International Development”. It deals with a zoonotic viral pandemic that wipes out millions across the globe. It’s not that long of a read, so let’s just take a quick walk through it, because it is indeed very eye-opening. The details are worth knowing.

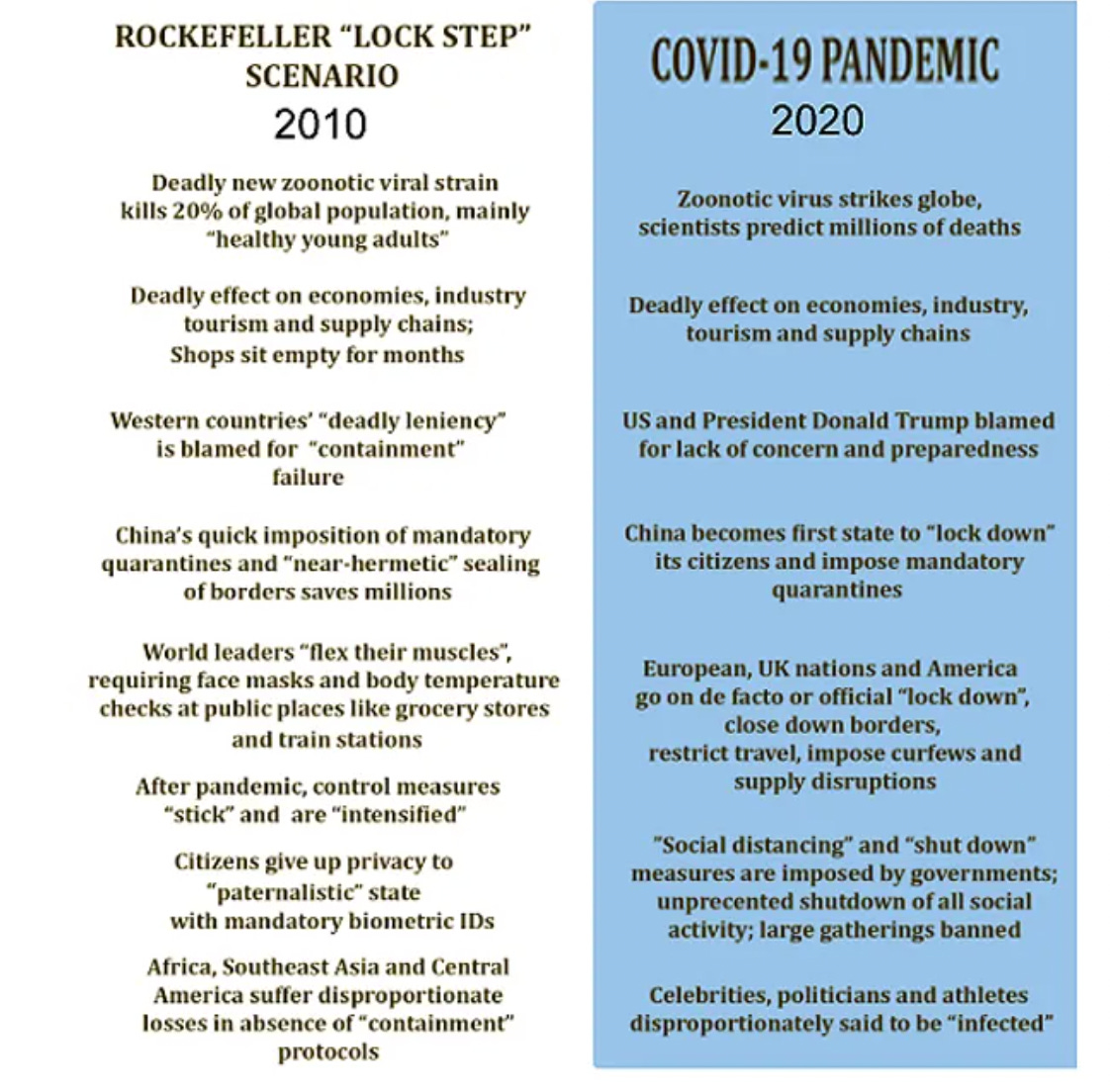

“A new influenza strain — originating from wild geese — was extremely virulent and deadly. Even the most pandemic-prepared nations were quickly overwhelmed when the virus streaked around the world, infecting nearly 20 percent of the global population and killing 8 million in just seven months, the majority of them healthy young adults. The pandemic also had a deadly effect on economies: international mobility of both people and goods screeched to a halt, debilitating industries like tourism and breaking global supply chains. Even locally, normally bustling shops and office buildings sat empty for months, devoid of both employees and customers.

The pandemic blanketed the planet — though disproportionate numbers died in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Central America, where the virus spread like wildfire in the absence of official containment protocols. But even in developed countries, containment was a challenge. The United States’s initial policy of “strongly discouraging” citizens from flying proved deadly in its leniency, accelerating the spread of the virus not just within the U.S. but across borders. However, a few countries did fare better — China in particular. The Chinese government’s quick imposition and enforcement of mandatory quarantine for all citizens, as well as its instant and near-hermetic sealing off of all borders, saved millions of lives, stopping the spread of the virus far earlier than in other countries and enabling a swifter post-pandemic recovery.

China’s government was not the only one that took extreme measures to protect its citizens from risk and exposure. During the pandemic, national leaders around the world flexed their authority and imposed airtight rules and restrictions, from the mandatory wearing of face masks to body-temperature checks at the entries to communal spaces like train stations and supermarkets. Even after the pandemic faded, this more authoritarian control and oversight of citizens and their activities stuck and even intensified. In order to protect themselves from the spread of increasingly global problems — from pandemics and transnational terrorism to environmental crises and rising poverty — leaders around the world took a firmer grip on power.

At first, the notion of a more controlled world gained wide acceptance and approval. Citizens willingly gave up some of their sovereignty — and their privacy — to more paternalistic states in exchange for greater safety and stability. Citizens were more tolerant, and even eager, for top-down direction and oversight, and national leaders had more latitude to impose order in the ways they saw fit. In developed countries, this heightened oversight took many forms: biometric IDs for all citizens, for example, and tighter regulation of key industries whose stability was deemed vital to national interests. In many developed countries, enforced cooperation with a suite of new regulations and agreements slowly but steadily restored both order and, importantly, economic growth.

Across the developing world, however, the story was different — and much more variable. Top-down authority took different forms in different countries, hinging largely on the capacity, caliber, and intentions of their leaders. In countries with strong and thoughtful leaders, citizens’ overall economic status and quality of life increased. In India, for example, air quality drastically improved after 2016, when the government outlawed high-emitting vehicles. In Ghana, the introduction of ambitious government programs to improve basic infrastructure and ensure the availability of clean water for all her people led to a sharp decline in water-borne diseases. But more authoritarian leadership worked less well — and in some cases tragically — in countries run by irresponsible elites who used their increased power to pursue their own interests at the expense of their citizens.

There were other downsides, as the rise of virulent nationalism created new hazards: spectators at the 2018 World Cup, for example, wore bulletproof vests that sported a patch of their national flag. Strong technology regulations stifled innovation, kept costs high, and curbed adoption. In the developing world, access to “approved” technologies increased but beyond that remained limited: the locus of technology innovation was largely in the developed world, leaving many developing countries on the receiving end of technologies that others consider “best” for them. Some governments found this patronizing and refused to distribute computers and other technologies that they scoffed at as “second hand.” Meanwhile, developing countries with more resources and better capacity began to innovate internally to fill these gaps on their own.

Meanwhile, in the developed world, the presence of so many top-down rules and norms greatly inhibited entrepreneurial activity. Scientists and innovators were often told by governments what research lines to pursue and were guided mostly toward projects that would make money (e.g., market-driven product development) or were “sure bets” (e.g., fundamental research), leaving more risky or innovative research areas largely untapped. Well-off countries and monopolistic companies with big research and development budgets still made significant advances, but the IP behind their breakthroughs remained locked behind strict national or corporate protection. Russia and India imposed stringent domestic standards for supervising and certifying encryption-related products and their suppliers — a category that in reality meant all IT innovations. The U.S. and EU struck back with retaliatory national standards, throwing a wrench in the development and diffusion of technology globally.

Especially in the developing world, acting in one’s national self-interest often meant seeking practical alliances that fit with those interests — whether it was gaining access to needed resources or banding together in order to achieve economic growth. In South America and Africa, regional and sub-regional alliances became more structured. Kenya doubled its trade with southern and eastern Africa, as new partnerships grew within the continent. China’s investment in Africa expanded as the bargain of new jobs and infrastructure in exchange for access to key minerals or food exports proved agreeable to many governments. Cross-border ties proliferated in the form of official security aid. While the deployment of foreign security teams was welcomed in some of the most dire failed states, one-size-fits-all solutions yielded few positive results.

By 2025, people seemed to be growing weary of so much top-down control and letting leaders and authorities make choices for them.

Wherever national interests clashed with individual interests, there was conflict. Sporadic pushback became increasingly organized and coordinated, as disaffected youth and people who had seen their status and opportunities slip away — largely in developing countries — incited civil unrest. In 2026, protestors in Nigeria brought down the government, fed up with the entrenched cronyism and corruption. Even those who liked the greater stability and predictability of this world began to grow uncomfortable and constrained by so many tight rules and by the strictness of national boundaries. The feeling lingered that sooner or later, something would inevitably upset the neat order that the world’s governments had worked so hard to establish.”

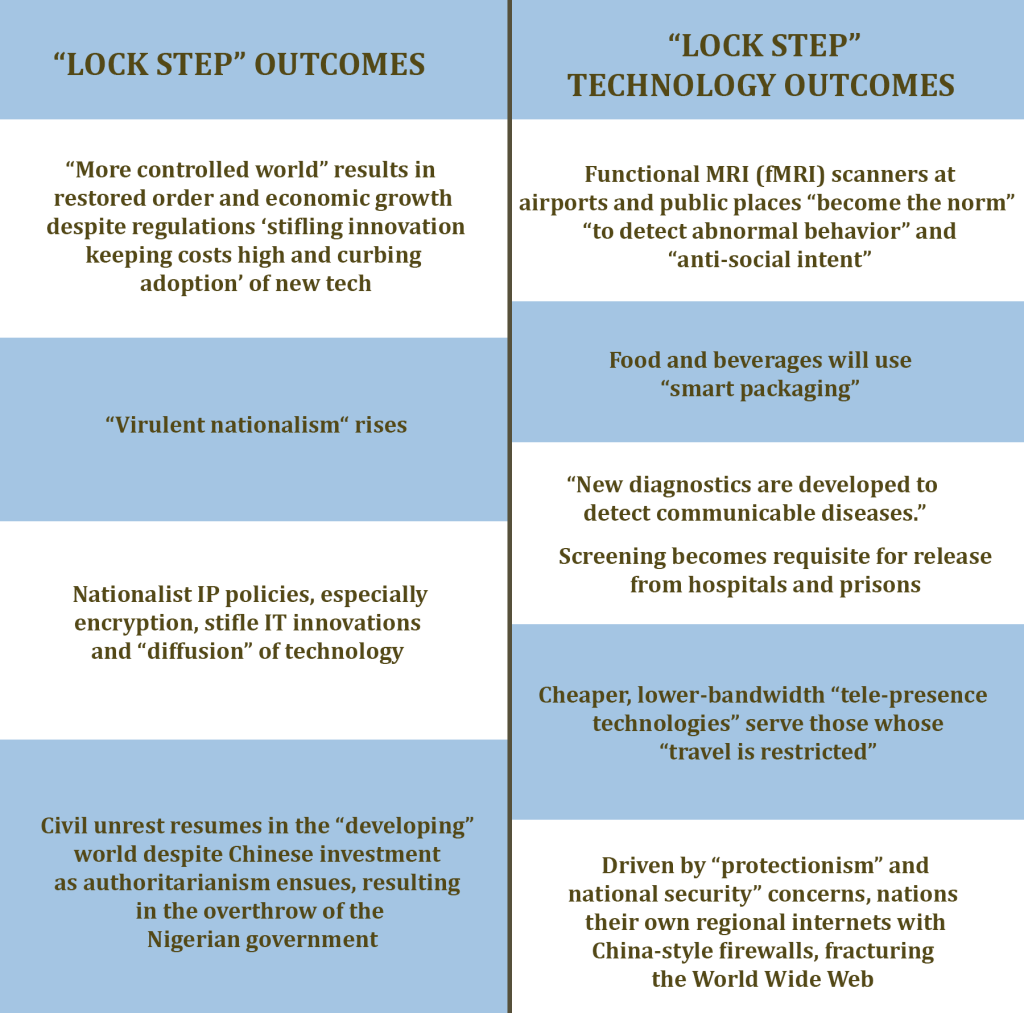

Here are our key take-aways from the “Lock Step” scenario, including a comparison to the coronavirus (COVID-19) event:

Is it starting to make sense now?